Days of Revolution and Recovery

Times were tough in post-World War I Berlin as rival parties and factions battled to fill the vacuum caused by collapse of the discredited Kaiser’s government. With much of the action in central areas of the city, the ever-observant Zehlendorfer Schacht noted unnecessary comic opera:

“The revolution in Zehlendorf started with the chairman of the Parish Council sending out invitations… The Parish Council, he said, had prepared a cheap popular lunch in an open-air restaurant situated on the borders of Zehlendorf, right on the arterial road from Berlin. When the revolutionary hordes came pouring out of Berlin, they would be attracted by this cheap lunch, appease their hunger and by the time they entered Zehlendorf itself would be as tame, so to speak, as lions in a state of repletion.”

Schacht, My First Seventy-Six Years

Grünau memorial stone for Berlin-Köpenick workers who were shot by counter-revolutionary troops of the Kapp Putsch in 1920. In this 2008 photo it was flanked by a street market and a public restroom.

In 1920, right-wing elements struck back. Fighting extended into suburban Köpenick. In that year, Robert Haberling sold his villa; property tax records are missing for the next seven years of turmoil. During that time Weimar Republic politicians and German economic leaders such as Schacht struggled to keep the ship of state afloat.

From 1923, Hjalmar Schacht and his colleagues worked to stabilize the German Mark. The story of wild inflation is well-known, but others were working on restoring Germany’s pre-WW I industrial and commercial preeminence.

On 31 January 1927 the Inter-Allied Commission of Military Control in Germany ended its administrative duties. Things were literally looking up as Junkers began air service in February to the oil boom towns of Baku, Teheran, Esfahan, and Bushire. As a sign of return to the old competition, when service began in the Persian Gulf city of Bushire, Imperial Airways of the United Kingdom had reached there a month earlier.

On 2 April 1927, as sound money policies took hold, the two-step German notary process recorded the intent to transfer ownership of Prinz-Friedrich-Karl-Strasse 11 (Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 after 14 September 1927).

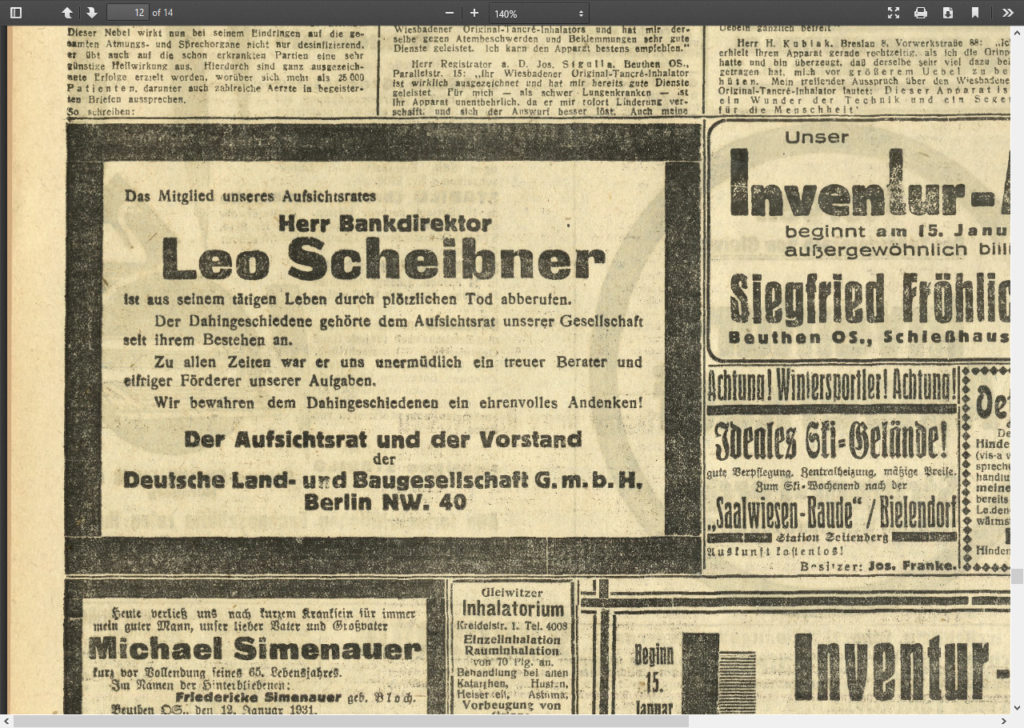

12 May 1927 brought a new face as owner of the villa, corporate director and head of personnel for Reichskreditgesellschaft AG, Leo Scheibner.

One day later, the German stock market crashed.

“The economic slowdown started in Germany about one year earlier than in the U.S. and the stock market had been on a declining trend since early 1927. The main reasons of the slowdown were the fall in profit margins due to excessive real wage growth and the large German borrowing abroad.”

Andrea Sommariva and Giuseppe Tullio published in the September 1989 issue of The Journal of Banking and Finance.

Leo Scheibner sold his home to his employer, the Reichskreditgesellschaft AG. (Mass-circulation Bild in 2012 stated that Scheibner sold the home to Industrieanlagen GmbH in October 1927.)

This is a good place to pause for a moment and note that this is not a complete history of the villa. There are many nooks and crannies that may be explored by someone who has time in Berlin to find the records of the Reichskreditbank, for example. For post-World War II history, someone with time in Washington, DC and vicinity may fill in the U.S. Army’s use in more detail than will be provided here later on.

It is possible that the property transfer was planned all along. It is also possible that the stock market turmoil may have put Bank Director Scheibner in awkward financial straights and that the transfer to his employer — a government-owned organization that specialized in distressed investments — relieved him of the unforeseen financial burden. (In 1908 he had donated five marks to the Deutsche Luftschiffer-Verband [German Airship Association], a modest contribution showing an interest in aviation by a young man early in his career. Donors from moneyed families were listed at ten to twenty times his amount.)

At some point in this period he became a director of the German Land and Construction Society, Inc. He resided at Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 until his death in 1931. In fact, the city directory shows that the property included Sven-Hedin–Strasse 7 and 9, as well. A gardener also lived on the premises. Construction of more villas continued along the tree-lined street.

14 January 1931

According to the city directory, the villa remained vacant from 1932 into 1934. In that last year, construction began on a house at Sven-Hedin-Strasse 7.

Neighborhood folklore, repeated in Bild in 2012, is that Hjalmar Schacht lived briefly in Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 during this period. This is not reflected in city directories or in Schacht’s autobiography. His daughter, Cordula Schacht, was born later, but in 2015 wrote that she does not recall her father speaking of that villa.