Days of Empire

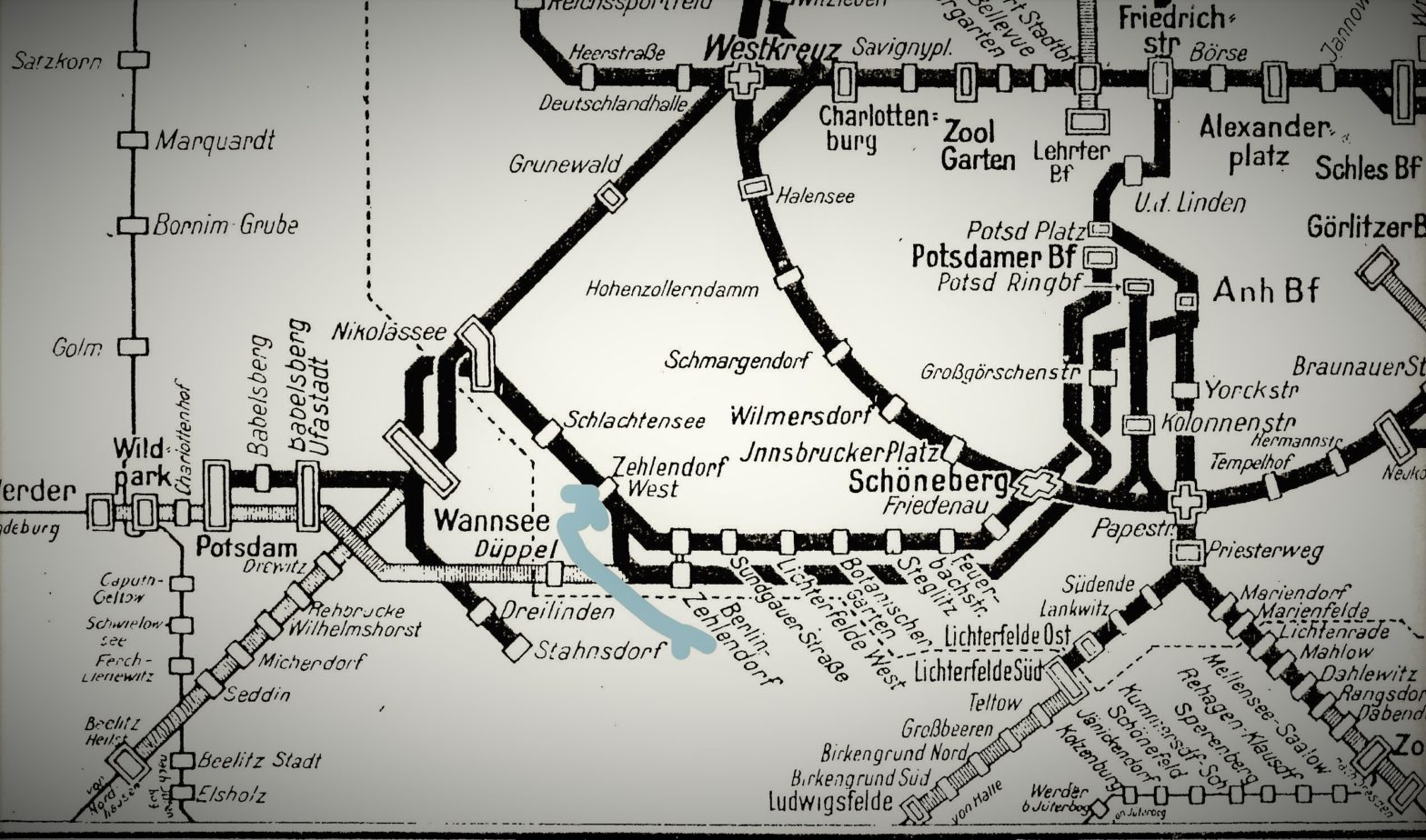

On 1 November 1904, after thirty years of steaming past, Wannseebahn suburban trains began stopping at a new station, Zehlendorf-Beerenstrasse. The station, since 7 March 1987 known as Mexikoplatz, was a joint project of real estate developers (Zehlendorf-West Terrain-Aktiengesellschaft), the local government of Zehlendorf and the Royal Prussian Railways. Trains rolled into the center of Berlin at the Wannseebahnhof, on the west flank of the major Potsdamer Bahnhof. After centuries as farmland, Zehlendorf-West was to become an elegant suburb.

By 1908 the famed Bankierzüge (Bankers’ trains) provided express service on the main line tracks into Potsdamer Bahnhof itself, speeding up commuter travel for customers from stations between Wannsee and Zehlendorf, including Zehlendorf-Beerenstrasse. [These tracks were later used for U.S. Army trains.]

In February 1914 design of a two-story, single family Landhaus, as large suburban homes had been labeled in Germany, was commissioned for property at Prinz-Friedrich-Karl-Strasse 11. Prominent Schlachtensee architect John Kruse designed the villa, as houses of this type were beginning to be called. Kruse’s best regarded pre-WWI project is a schoolhouse on Dübrowplatz. The German Empire, united only in the previous two generations, was thriving. Its products were sold around the world, to the consternation of older empires. Architects responded with “heavy” buildings that almost swagger. Construction manager was listed as Robert Haberling of Berlin.

Photo credit:

Haberling GmbH

For an English language history of the firm that Robert Haberling founded:

https://www.haberling.de/en/company/history/

As European empires and the new Pacific powers maneuvered for advantages, the design and construction of the landhaus at Prinz-Friedrich-Karl-Strasse 11 got underway. The project’s developers could not have missed the increasing tension, but it had been a century since the Continent had been caught up in global strife. Prussia had won quick wars since then. Germany was far advanced, it seemed, in every respect since Napoleonic days.

Robert Haberling’s moving and relocation managers knew that European economies were now so integrated that a Continent-wide war was unthinkable. And when the workers building the proud landhaus chatted on their lunch break, they had heard that Socialist parties of Europe had committed to calling a General Strike that would halt the troop trains and silence the guns by starving them of munitions.

Nevertheless, on 28 June 1914, a local incident in Sarajevo – the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand – led to a month of bungled diplomacy and then the multi-front war that earlier Prussian leaders had avoided was underway. Suddenly, Germans were fighting in the Pacific, the Mediterranean, Africa, Asia, and on two fronts in Europe. And they were doing fairly well against the commercial enemy, the British Empire. The threat of Slavic hordes from the East combined with initial success in the West to sweep commercial interest and labor interest in peace efforts off the table.

Not every worker was called up or diverted into war industries immediately. After all, many expected the war to be short, as the previous strife with Denmark and France had been. On 13 March 1915 the house at Number 11 was turned over to its first owner, Robert Haberling. The property also included the lots for Numbers 7 and 9. Walking past their expanse, it was about a ten-minute stroll to the new commuter train station. Along the way, a drugstore and other businesses had sprung up.

As the Royal Navy and British colonial troops methodically cornered, captured or killed overseas German forces and shut down trade routes, errors and opportunism by both sides brought European movement to a grinding halt. Closely observing developments was a young banker who had also lived in Zehlendorf-West since 1911. Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht was to recall in his memoirs four decades later that:

“…the great tragedy of the war was unfolding at the Front. On my way from the banking quarters of Berlin to catch my train home at the Potsdam Station I would pass the long queues of people in front of the shops with the badly lit windows, catchpenny articles and ersatz goods which now replaced the magnificent displays and excellent quality.”

Schacht, My First Seventy-Six Years