— by R. W. Rynerson – 2013

Author of “A Man Without a Country”

A young American who put himself crosswise with his country was on people’s minds a century and a half ago. In Edward Everett Hale’s story, “Philip Nolan” was the fictional U.S. officer out West who was sentenced to live the rest of his life cut off from the country that he loved. Whether intentional or not, Hale’s work marked a change in the psychology of exile, a change now confronting fugitive Edward Snowden.

Prior to that era, if a fugitive or political refugee journeyed beyond the outer limits of the postal system, they could disappear. They could begin a new life if they wished, as many Americans who fled to Latin America did. Colorado pioneer backwaters had their share of people from Europe or Back East with gaps in their life stories.

Things changed by the end of the 19th century. We congratulate ourselves on today’s level of communication, but the telegraph and steam power created a web from which exiles or even those temporarily “away” could never completely slip through. The image of the Northern Pacific’s trans-continental Fast Mail thundering through the night from Chicago to the Pacific mail steamer waiting in Seattle grabbed generations of Americans — not only because it was delivering Sears & Roebucks catalogs — but also carried letters of all kinds. And it carried publications of all kinds, too, including radical political journals. Steam on the seas and on the rails had lowered postage rates dramatically. Even faster, telegraph messages spanned time zones and oceans. Thus exiled Sun Yat Sen could pick up the Denver Post in 1911, and receive news that the Imperial Chinese government had been overthrown two days prior.

In the 20th century “Man Without a Country” phenomenon, Portlander John Reed achieved fame for insider reporting on the 1917 Russian revolution — notably the readable book 10 Days That Shook the World. But carried along with revolutionary fervor, he participated in the founding of the Communist movement in the U.S., ended up without a passport, and lived his last years in the new Soviet Union. He began to see the bright promises of the revolution being deferred or trampled upon. Distrusted by some of the new leaders, he was sent on political missions when he should have been receiving medical care, so conveniently died a hero.

John Reed and other foreign Communists safely dead are memorialized in the wall of the Kremlin (2010 photo above), behind the reviewing stands where currently serving dignitaries observe the masses on parade. In 2010, a security guard rolled his eyes as yet another American asked which plaque was John Reed’s. He had only heard of him through tourists.

In the 1930’s American and British leftists who followed Reed’s path into Russia found an expatriate community that was at once tight-knit and supportive, but also threaded with envy and intrigue. It seemed that the more successful someone was at integrating themselves into Soviet society, the more they were criticized by others. Thanks to letters intercepted by British MI5 – communications were being monitored even back then – we can read of the sense of isolation in Moscow that closed around British Communist expat Rose Cohen and her child. Her husband in a purge trial, then herself on trial, her son sent to an orphanage, and finally in 1937 her execution.

In East Berlin of the 1950’s and 60’s, a similar English-speaking expatriate community developed. Many of these people retained their national passports, but some, like journalist Victor Grossman (Harvard ’49 as Stephen Wechsler) were limited in their travels by decisions they had made — in Grossman’s case, defecting from the U.S. Army in 1952. Grossman made a life for himself in the German Democratic Republic, but even so, was caught in an awkward situation when that country was merged into the Federal Republic of Germany. It created an ongoing crisis for him until he was able to work out a belated “less than honorable” discharge.

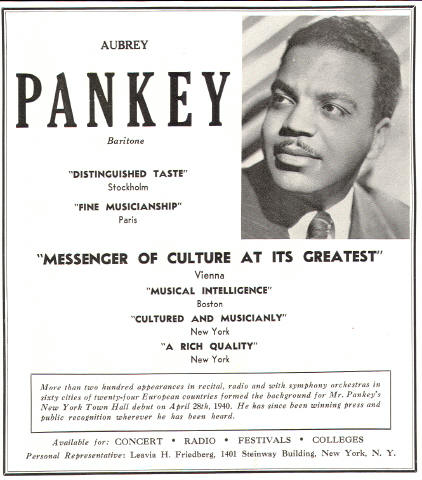

Among the Americans he met there were two talented men who never fit in. Aubrey Pankey, a trained classical singer involved in left-wing politics found he was unwelcome at home and Pankey’s wife, an activist, became unwelcome in France. In Stalinist Eastern Europe, with its emphasis on high culture, he was welcomed on the concert stage. But his career gradually faded and by 1970 the government’s Socialist Unity Party wanted new faces. Pankey was killed when his car crashed off an East German road into a tree as he drove home alone early on a Sunday in 1971. “Tired, speeding, alcohol” the police report said. Local media ran a carefully worded inch or two from the official press agency – except for the papers that ignored his passing.

A few months after the classical musician’s death, a different, modern musical face turned up to live in East Berlin. Denver newspaper readers are familiar with the story of Wheat Ridge resident Dean Reed, but he is little known to Americans otherwise. His blend of rock and folk styles fit the new image that the GDR government party was developing. Reed was a genuine star and still has loyal fans around the world – he is soon to be inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame. But his career and life in East Berlin grew increasingly difficult as politics changed his personal and working environment. He died alone, by drowning, in 1986, his anxieties charted by electronic eavesdropping.

www.deanreed.de/deutsch/index.html

As of this writing [2013], Edward Snowden has a series of choices to make. If he chooses life as an exile, he may find that his voice for the cause that he espouses fades rapidly, especially if he lives in a country that requires political manifestations that suit the current government. And, beyond that choice, he would have to decide whether to settle in to be a part of his new country — worry about the price of bread and celebrate neighbors birthdays — or remain an outsider, always reaching out for attention. If he chooses the latter path, and if his host government does not dramatically change policies as did Rose Cohen’s or Victor Grossman’s, based on the experience of others, he has 15 to 17 years of declining relevance, tied crosswise by the World Wide Web between his home country and his hosts. He may then ask himself what further life waits for a man without a country.

=================================================

References:

Illustration of Edward Everett Hale from Cyr’s Fifth Reader, Ginn & Co., copyright 1899, courtesy of Alice Otto.

Callaghan, John and Phythian, Mark; “State surveillance and communist lives: Rose Cohen and the Early British Communist Milieu”; Journal of Intelligence History; published by Taylor & Francis; Abingdon, Oxon, U.K.; June 2013.

Grossman, Victor; Crossing the River; University of Massachusetts Press; Amherst and Boston; 2003.

Reed, John; 10 Days That Shook the World; International Publishers; New York; 1967 edition.