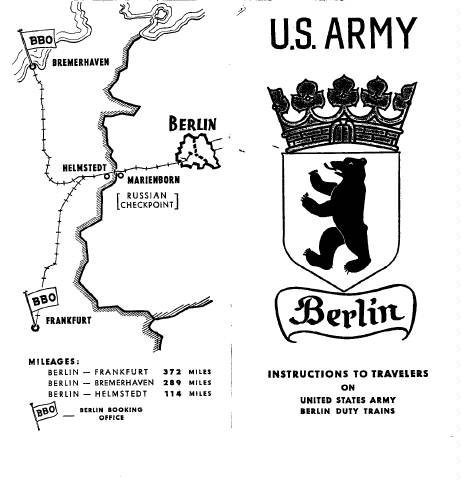

In exchange for my travel voucher and orders from the Replacement Battalion in Frankfurt, the Rail Transportation Office in the Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof presented a ticket in this envelope. I studied the map for a moment– because of my interest in history and geography I had some idea of the situation in Germany, but it had been an abstract concept until that evening in June, 1969.

My own situation at that moment was peculiar. Trained as a Personnel Management Specialist, I had turned up in Frankfurt at a moment when the Berlin Brigade was short of Russian-English interpreters. I did not know that then. All I knew is that we all grew tired of sleeping in our uniforms in the replacement facility, being called out for formations at all hours, sometimes in a gray drizzle. Names would be called out, and people would disappear into interview rooms, appearing later with orders. Then they were marched out of the gate and across the street into the care of the Deutsche Bundesbahn.

Leafing through my personnel file, the clerks in the pre-War (as in the Kaiser time) kaserne across from the Hauptbahnhof had given me my choice. Armed Forces Radio in Frankfurt needed a news announcer. I had experience as a student journalist. Which would I like to do? Fame (or at least name recognition) in Frankfurt, or an unidentified job in Berlin that “involved a lot of train riding and speaking some Russian.” I asked the clerk whether the Berlin assignment was in a Linguist slot, because the Army’s excellent language test said that I was not qualified for that. I was told that I should mind my own business. Apparently the idea of a person being given a choice between two intriguing possibilities was enough of a break with military tradition– asking questions about the jobs was too much.

In that moment, I applied what little I knew about Frankfurt — it was dirty, it had punctual streetcar service (I had found a window high on the kaserne wall where I could look down into the street– out of boredom and curiosity I had been dissecting street life, and that included calculating the headway (wagenfolge) of the streetcar line, the hauptbahnhof was busy, and the “women” who came into the NCO club to sponge drinks off the replacement troops were not really women at all. The latter information came from a German maintenance worker who noticed my curiosity about everything, and pointed out that these female impersonators were not at risk of being found out by the young soldiers who they charmed, since none of us replacements could leave the kaserne. He thought that my time was better spent watching the strassenbahn.

On the other hand, I reasoned, with the political situation being what it was, our government would probably treat the Berlin troops first class. And, I had read a bit about Berlin, while Frankfurt meant little to me (the year 1848 came to mind, but I could not think of anything else that had happened there). The Hessians had fought on both sides in the American Revolution and there would be some things to follow up on there, but I could think of dozens of questions about Berlin. If I went to the divided city, it seemed that any job, including cleaning latrines, would be better than any job in Frankfurt.

So I told the interviewer that I liked riding trains, and that it was true that I could speak, read and write a little bit of Russian. Orders were written for me to join a cross-section of replacements on the train to Berlin. And then I was told to miss the shipment?

Miss the shipment? That is one of the worst sins in the military. And I was being told to do that. I was introduced to Specialist 5 McCarthy, who turned out to be the Berlin Brigade’s transportation “fixer” in Frankfurt. It would be okay to miss the shipment, I would just go up on the next night’s train. At the time I did not know it, but I was being diverted from potentially being snared by the Berlin personnel office from being used to fill a vacancy that they had. When I would arrive a day late in Berlin, I would not be met by the Adjutant General Corps representative of personnel; instead I would be met by a Transportation Corps man who would push me quickly through the entry process in Berlin, not permitting the personnel staff time enough to realize what had been done to them.

I watched the other soldiers march out the gate and across to the train station. I felt a twinge of worry.

After killing another day, on the next evening after dinner I was pointed in the direction of the Rail Transportation Office (RTO), and I walked to it by myself, feeling a little lonely after being shepherded everywhere for a week from Fort Dix, New Jersey to this street corner in a foreign city. Now, I read the ticket folder, opening it to study the information inside.

As I scanned the contents, I read the list of train staff. The Interpreter, I learned, was an individual “fluent in Russian, who is designated to act as translator-interpreter for the train commander…” My head spun as I realized that this was the job to which I was being assigned – a Linguist position. For a moment, I thought about walking back across the street and telling the clerks in the kaserne that they had made a bad mistake. Then I thought about what I had concluded about Frankfurt versus Berlin. I walked on out to the train platform (bahnsteig). This problem could be solved later, but at least I would get the train ride to Berlin before they threw me out.

As the electric locomotive moved the Duty Train smoothly out of the railyard, I watched every detail outside of the window, eager to feel Frankfurt and the kaserne receding further and further behind me. Finally I fell asleep, partly out of exhaustion and partly out of relief at being on my way, even if to an undefined future.

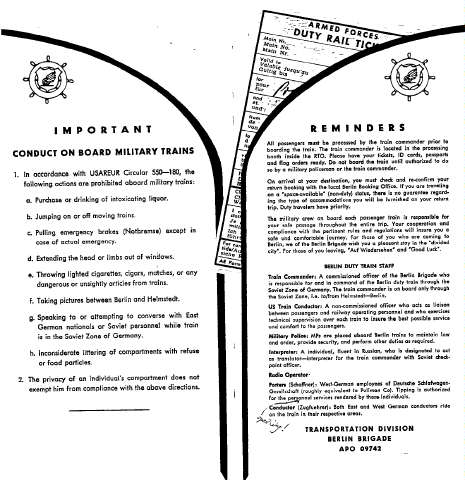

IMPORTANT

CONDUCT ON BOARD MILITARY TRAINS

1. In accordance with USAREUR Circular 550-180, the following actions are prohibited aboard military trains:

a. Purchase or drinking of intoxicating liquour.

b. Jumping on or off moving trains.

c. Pulling emergency brakes (Notbremse) except in case of actual emergency.

d. Extending the head or limbs out of windows.

e. Throwing lighted cigarettes, cigars, matches or any dangerous or unsightly articles from trains.

f. Taking pictures between Berlin and Helmstedt.

g. Speaking to or attempting to converse with East German nationals or Soviet personnel while train is in the Soviet Zone of Germany.

h. Inconsiderate littering of compartments with refuse or food particles.

2. The privacy of an individual’s compartment does not exempt him from compliance with the above directions.

REMINDERS

All passengers must be processed by the train commander prior to boarding the train. The train commander is located in the processing booth inside the RTO [Rail Transportation Office]. Please have your tickets, ID cards, passports and flag orders ready. Do not board the train until authorized to do so by a military policeman or the train commander.

On arrival at your destination, you must check and re-confirm your return booking with the local Berlin Booking Office. If you are traveling on a “space-available” (non-duty) status, there is no guarantee regarding the type of accommodations you will be furnished on your return trip. Duty travelers have priority.

The military crew on board each passenger train is responsible for your safe passage throughout the entire trip. Your cooperation and compliance with the pertinent rules and regulations will insure you a safe and comfortable journey. For those of you who are coming to Berlin, we of the Berlin Brigade wish you a pleasant stay in the “divided city”. [Note use of the German style for quote marks inside the sentence-ending period.] For those of you leaving, “Auf Wiedersehn” and “Good Luck”.

BERLIN DUTY TRAIN STAFF

Train Commander: A commissioned officer of the Berlin Brigade who is responsible for and in command of the Berlin duty train through the Soviet Zone of Germany. The train commander is on board only through the Soviet Zone, ie. to/from Helmstedt-Berlin.

US Train Conductor: A non-commissioned officer who acts as liaison between passengers and railway operating personnel and who exercises technical supervision over each train to insure the best possible service and comfort to the passengers.

Military Police: MP’s are placed aboard Berlin trains to maintain law and order, provide security, and perform other duties as required.

Interpreter: A individual [stet], fluent in Russian, who is designated to act as translator-interpreter for the train commander with Soviet checkpoint officer.

Radio Operator: [no information offered]

Porters (Schaffner): West-German employees of Deutsche Schlafwagen-Gesellschaft (roughly equivalent to Pullman Co). Tipping is authorized for the personnel [stet] services rendered by these individuals.

Conductor (Zugfuehrer): Both East and West German conductors ride on the train in their respective areas.

TRANSPORTATION DIVISION

BERLIN BRIGADE

APO 09742

…………………………………………………………………………………….

My notes on Conduct and on the Duty Train staff positions in 1969:

Conduct: these clear-cut rules were enforced. At the booking office in Berlin we had a blacklist posted over the inside of the ticket window, naming people who were no longer authorized to ride the duty trains. They would have to pay for their own air travel or drive the stressful Autobahn between Checkpoints Bravo and Alpha.

Train Commander: typically a First Lieutenant. As a rule of thumb, there was a core of the train commander staff who were Transportation Corps officers, augmented by officers from other branches. The quality of the latter varied greatly. As an interesting sidelight, the folder does not mention the Senior Officer on the train. Each night, about the time that the train began to roll, one of the military train crew would work their way through the corridors to the compartment of the officer who had been determined to be the most senior “combat arms” officer on the train that night. We would not necessarily know who that was until we had gone through every passenger’s paperwork.

Reactions when they were notified varied. Some were honored or intrigued by this brief distinction, adding a bit of color to their account of riding the famous Duty Train. Some were concerned about whether they might have to actually do something– there were hundreds of uneventful trips, but if something happened, what were they expected to do? After all, if you were in pajamas ready for bed, would you be pleased when a bemused Private First Class knocks on your door and announces that you have just been put in theoretical charge of two hundred rather diverse Americans going through a part of the world possibly unfamiliar to you?

US Train Conductor: In contrast to the Train Commander position, I believe that this job was always filled with a “trained” railway conductor from the Transportation Corps. Army rail operations go back to the U.S. Civil War, when General Herman Haupt organized the Railroad Corps after numerous incidents and fiascoes involving Federal troops and railway personnel. The British, with a smaller military in mind, combined the Conductor and Commander jobs into the post of Train Conducting Warrant Officer (TCWO). These, too, were professionals.

At least one of the conductors who I met was continuing to accumulate seniority on a U.S. railway, because he had been drafted for the Korean War. They worked through from West Germany (I believe from their base in Mannheim), so when the Berlin-based train commander was turning back in Helmstedt, the Train Conductor was in charge west of there.

Military Police: These soldiers came from the Railway Military Police unit based in Frankfurt, and were supplemented with men from the Berlin 287th MP Company on the Berlin-Helmstedt segment.

Interpreter: This was the only position which would be filled by either a German civilian or a U.S. soldier. Due to the shortage of U.S. personnel who could qualify as Russian-English interpreters, at least three Germans worked the trains while I was there. One of them, Mr. Frank or Francois Pachurka was reported in 1990 news stories to have become the interpreter on the last train. Another was most senior, Willi Schmoranz, who originated the special “Flag Orders” in the early days of the train, after initially typing all the lines of each order on his Cyrillic manual typewriter. Peter Rzymkowski was the third and youngest.

Radio Operator: It would seem that this position is self-explanatory, but there were some special reasons to value this soldier’s work in the crew. The radio operator was usually the only person who knew where we were in the night. He would radio what railroaders call an “O.S.” signal to the Brigade Headquarters as we went through each station. By this means, Brigade could tell about where we were, and that we were (hopefully) moving as planned. While passengers assumed that we always knew where we were, our work would distract us, and a look out the window into the dark night of dimly lit East Germany would not help. By checking with the radio operator, we could know which landmark to watch for or feel ourselves clattering through next on the ocean of rails.

The radio operator did his work through a book of the U.S. Army’s basic, throwaway codes. When a significant military activity was observed, such as a Soviet Army convoy waiting at a grade crossing (level crossing in British terminology), we would come up with a consensus as to what we had seen, and the radio operator would encode a message to Brigade. Of course, this mainly could help in terms of the number of occurrences– we were not providing detailed intelligence by this coincidental method.

My favorite mental image is of watching out the open window on a warm night, and spotting a line of Soviet trucks (Zil-157 or related types) stretching into the dark, waiting for us at a crossing.

The German railway employees used to do things to irk the Soviets, and it is possible that they chose to hold this convoy up on purpose. The typical crossing in East Germany was an old Deutsche Reichsbahn facility with hand-operated gates, which could also be a legitimate reason for bringing them down well before a speeding passenger train was due. For whatever reason, some of the Soviet soldiers had dismounted for smokes. Against the glare of their headlights, they were cardboard silhouettes to us. They would have seen our conventional Reichsbahn diesel engine, and then the long train of dark-green cars, with their headlights lighting our Transportation Corps lettering on each car.

And then we were in the dark again…. and where was that crossing? With the help of the radio operator, we figured out a likely location and he sent the message off. The Soviet soldiers mounted their trucks and headed off across the tracks behind us. Somewhere, the message worked its way through our intelligence system, and, as always in Berlin stories, we can assume that somewhere an East German or Soviet radio monitor sat at a desk and worked out a decoding of our message. Since we changed codes nightly, this probably required more work than it was worth.

Thus for a few moments, the two wary armies would face each other, and our tiny contact would be noted by both sides. The Cold War was often like that.

Porters (Schaffner): I had occasion to chat with several of these men, some of whom had been working the military trains for years. During my time on the Duty Train, there was no food service car, but the porters sold snack items through the train. My favorite memory is of getting up early when I was a passenger on the Bremerhaven to Berlin train (about 4:00 a.m.), when I smelled a wonderful coffee aroma. Unlike the crowded Frankfurt – Berlin train, this train rarely carried many passengers, and on this winter trip, I was among the few on board. Who was having coffee?

I pulled myself together and went through the corridor to the end of the car, where the schaffner was heating coffee on a tiny gas hotplate. No one else was moving around… we were still inside the Soviet Zone, traveling through the dark. He pulled out an extra cup and invited me to join him, as his guest. We rode along and talked railroading. He had once worked the NATO sleeper, which ran between Paris and Bremerhaven’s Port of Entry (POE) in connection with the S.S. United States. This was roughly a two-week round-trip, with the layover on the Paris end of the turn. He had plenty of time to sightsee! He also recalled sleeping in the car on his layover, piling on the blankets during cold winter nights (Paris can be cold and damp). His wife was not very pleased with his assignment, but it was a premier piece of work, and tips were good.

There have been a number of times that I was awake in the middle of the night on a train or a ship. This quiet conversation with a man who loved his work, with good coffee, was one of the best.

Conductor (Zugfuehrer): Most of the trip through East Germany, the Zugfuehrer rode in his own compartment (abteilung) in splendid isolation, with nothing to do. Our Army train conductor would deal with him on operating matters, and that was it. I would have liked to have learned much more about his work on this peculiar assignment, but I was not on the trains long enough to do so.

— Robert W. Rynerson

Rail Transportation Office

Berlin Brigade, 1969