“His terms of dealing with them had always been service terms: the odd, boyish, sometimes silly service language that came out of their exclusive world, for nobody else to understand. Behind this language, you could take refuge from the fear and reality of the business.”

H. E. Bates; Fair Stood the Wind for France; 1944.

Between the bright lights of the Ku’damm and the symbolic confrontation points of Cold War “Frontstadt Berlin” lies the green buffer of the Tiergarten, parkland and the city’s zoo. This part of the city is quiet as a cemetery in the pre-dawn hours. And that is appropriate– it is the symbolic graveyard of the Third Reich. It is a place where military language fails.

— R. W. Rynerson

Making signs that we are about to leave gets no response from “Herr Ober” — the flattering term of address for all waiters in Germany in this era. We stand and theatrically start to put on our jackets against the early morning coolness that awaits us. The check, “die rechnung”, the reckoning as it is called, comes and our little troop heads out onto the eerily quiet boulevard.

It is chilly now in the last hour before dawn. That’s good, we agree, as we wait for a traffic light to complete its cycle while a lone taxi races through against the yellow. The cool start will make it more comfortable when the sun comes up. In the meantime, we can shiver a bit.

As we walk past the Beate Uhse store, stereotyped as symbolic of the purported German drive for efficiency in all things, we alternate conversations in pairs. Unlike our time around the table, it is difficult to all participate in one conversation. It is easy to notice that our military hosts lapse into a kind of alternative language when they chat with each other, relaxing their attempt to speak standard English with us. While they talk about “u/i Zils” and “Grooneybushes” and “helichoppers” and try to figure out whether “Herms” is a term of cute endearment regarding the Germans or an ethnic slur, we maneuver to take the opportunity to talk with Michèle.

But just as we begin to ask your questions, she stops us on the footbridge over the Landwehr Canal for a moment, pardons herself, and asks our guides which way they plan to take us. It seems that there is more than one way to walk from this point, each way having its pros and cons.

This path is heavily trodden during the day and there are many distractions on a sunny day in the park. At this hour, the only distractions are the nocturnal sounds of nearby zoo animals. Around us, the young trees are a reminder that some of the last, grim combat of World War II took place here. Or, more practically, we are reminded that Berlin’s trees that survived the shooting were scavenged for firewood in the miserable winter of 1945-46.

We were born, we realize, about the time these trees were planted. Our conversation circles back to some of the family history — each of our family histories. We had learned around the table in the Alt-Berliner that each of our families had put their lives on hold for World War II. And each of us had begun our lives — had our lives begun — as a part of our families’ great hopes in the first post-War years. When these thoughts collide with our conversation about the age of the trees we fall silent.

“I wish that I could say something profound about the trees,” Robert comments. It sounds matter of fact, meant to be a bit flippant. But we notice that he has drifted back to take Michèle’s hand and she responds with a tight grasp. Profundity comes not only in words, but in human touch.

The young couple hold onto each other — not casually or to flirt — but tightly. When we talked about their families’ stories, we learned that their lives came of out of the havoc and hell that flamed to an end in these few hectares. Now they hold each other as they sense the history of this place, or perhaps — as our guide murmurs — as they try to visualize a future in this city that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev — not a man who would hide behind technical speech — had not long before called “the most dangerous place on earth.”

Or what about their futures? Their aspirations? They had left behind childish things in their hometowns, swept by the current of history into this city where an eventual settlement of World War II issues had been stalled for a quarter of a century. Chess games played by world leaders before they were born had continued into a stalemate that focused on streets that we now walked with them. Now they spoke in foreign languages — even thought in foreign languages — used military or diplomatic jargon without being conscious of it — and yet were strangers also in this strange land. No wonder they held tightly to each other.

Great excitement at the Taverne tonight. About two a.m. we get the terms of the Russian-German pact. It goes much further than anyone dreamed.

Joe [Barnes of the AP], who is shaken by the news though he is the only one here who really knows Russia, and I argue the points. We sit down with the German editors. They are gloating, boasting, sputtering that Britain won’t dare to fight now, denying everything they have been told to say these last six years by their Nazi lords. We throw it into their faces, Joe and I. The argument gets nasty. Joe is nervous, depressed. So am I. Pretty soon we get nauseated. Something will happen if we don’t get out. … Mrs. Kaltenborn comes in. I had made a date with her for three a.m. I apologize. I have to go. Joe has to go. Sorry. We wander through the Tiergarten until we cool off and the night starts to fade.”

— William L. Shirer’s Berlin Diary recounting the night of 23 August 1939 and the hours that followed.

We have wandered past the semi-restored Scandinavian embassies that now house Military Missions to this occupied city. When Joe Barnes and William L. Shirer went for their head-clearing stroll, the military attachés assigned to Berlin would have been firing off dispatches to their home governments. Lights would have been burning throughout these buildings. Now they are dark, the upper floors partly supported with extra timbers to prevent damaged sections from collapsing.

Our guide now explains that we are headed into the heart of the Tiergarten. As he says that, the Siegessäule, the Victory Column, looms in pre-dawn light before us, the monumental column celebrating the Prussian-German victory over France in 1871. Like two Old West gunfighters who had decided that there wasn’t room for both of them on the Continent, France and the newly united Germany had fought it out while other nations stood by.

Our guide reminds that this Prussian-led victory had changed everyone’s perceptions — the Germans’ view of themselves and the world, as well as the world’s perception of the Germans. Hitler had ordered the symbol of victory moved to this site at the intersection of broad boulevards where it would dominate its surroundings and make a statement as his military units marched past it for the newsreel cameras.

“That is not all bad,” murmurs Michèle, who has been quiet since we rejoined the pair. We turn to her, each thinking to ourselves that what a citizen of France has to say will be interesting.

“I am very moved by it,” she says quietly, “and so are my Berliner friends…”

Our sleepy eyes widen as she delivers this solemn statement. Then her dark eyebrows slant upward and a grin flashes across her face as she adds “… moved to not trust politicians who believe in their own grandeur.”

Of course, she referred to Adolf Hitler, but perhaps she also meant Charles de Gaulle. The general had saved France from itself more than once, then held on to power as the indispensible man. Her generation in France had tackled his aging government in ’68 head on, almost toppling the French Republic.

This has become the place for the annual Western Allied parade. There is no sound of marching boots on the boulevard now, nor do the shadowy figures of earlier evening hours remain along the dark margins of the sidewalks. Dead-ended at the Berlin Wall and the Brandenburg Gate, this street, our guide explains, has little traffic value, but is a useful rendezvous for those seeking illicit pleasures.

The night before I drove in one of the press cars which followed directly behind Hitler as he opened the “Via Triumphalis”– i.e..the broad avenue which is successively called Unter den Linden, Charlottenburg Chausee, Bismarckstrasse, Kaiserallee, to Adolf Hitler Platz. The whole avenue was bathed in light, and flags and banners were displayed in countless numbers…

— AP Bureau Chief Louis P. Lochner on 26 April 1939, quoted in Journalist at the Brink.

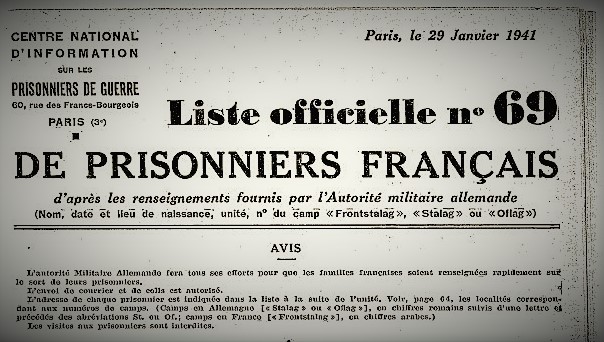

We turn onto the now empty Strasse des 17 Juni, and look ahead toward the Brandenburg Gate. Photographers with telephoto lenses have fooled us into thinking these things are close together. Now we see that they are not, giving us a hint of the monumental scale of Hitler’s dreamed of Germania, his world capital that would replace cozy Berlin. Michèle’s father had labored on later elements of the Germania project as a Prisoner of War.

It is hard for us to grapple with the scale of this now empty boulevard. A lone auto zooming past gives us some feel for its proportions. Robert has recently read The Last Battle and comes up with another way of visualizing this space. As the Red Army converged on this area, General Ritter von Greim and aviatrix Hanna Reitsch landed a small plane on the East-West Axis. It was pointless daring, but the sort of thing that impressed Hitler. He elevated von Greim to Field Marshall in the almost extinct Luftwaffe.

We walk toward the sunrise, quiet with our thoughts.

Bibliography:

Lochner, Louis P.; Journalist at the Brink; XLibris; www.XLibris.com; 2007.

Ryan, Cornelius; The Last Battle; Collins; London; 1966.

Shirer, William L.; Berlin Diary; Alfred A. Knopf; New York; 1941.

Meeting the sunrise

In Berlin, there’s usually a kniepe or a konditorei around the corner when we walk, ready with a beer or a coffee. But here in our hour in the focal point of Twentieth Century German history, there is nothing. The Strasse des 17 Juni seems to go on forever in this segment, bereft of visual metaphors or ornamentation.

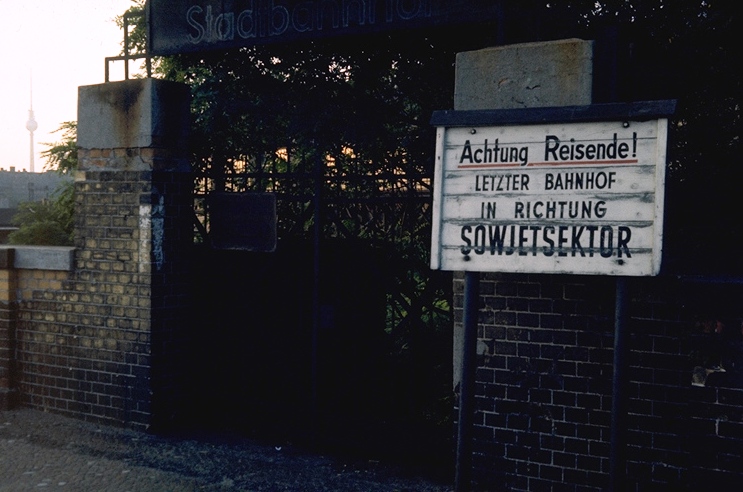

There are hopeful signs, though: visual symbols of the Cold War inch closer with each step.

There are hopeful signs, though. The Soviet war memorial looms larger; the Brandenburg Gate is taking shape, the East Berlin television tower: visual symbols of the Cold War inch closer with each step.

Our guide explains that we will have to skirt the provocatively placed Soviet memorial, sometimes sarcastically known as “the Unknown Looter” to Berliners. It was built in the British sector, creating complications ever since. Now security around it has been tightened since the 1970 shooting of a Soviet soldier by a neo-Nazi who hoped to provoke a halt in the negotiations that were beginning to bring a legal end to World War II. Now, in addition to the Soviet guards on duty, British Military Police and West Berlin city police patrol the vicinity. Running into us on our inexplicable mission, Americans and one Frenchwoman, would have been the sort of complication that made occupied Berlin so complex.

Quiet at sunrise, the Soviet War Memorial in the British Sector – guarded by Soviet soldiers who were guarded by British soldiers who were guarded by West Berlin police.

On November 7, 1970, a Soviet sentry on duty here was seriously injured by a shot fired by a German nationalist radical. These summer scenes reflect the added security measures that cause a detour in our journey.

The absurdity of this guarding of the guards guarding, serious though it is, reminds our guide of some of the Berliners’ dark humor regarding the divided city’s situation.

“Why are shoes priced so high and streetcar fares so low in East Berlin?”

Robert has already heard this one and replies: “Because you can report to work barefoot, but you have to get there on time.”

“Who leaves East Berlin every day and moves West?” Robert tosses back.

“Herr Sun! And in 1970 over 17,000 citizens of the German Democratic Republic,” our guide ripostes.

This banter is really the last tattered remnant of the random conversations that have helped to keep us awake in the still hour that ended the night.

The sun – yet below the horizon – already has painted a rose pastel sky that we share with no one. Well, no one except for the GDR border guards watching us from the other side – darueber – as we approach the Berlin Wall and the Brandenburg Gate.

Bibliography:

Eulenspiegel; Sternstunden des DDR-Humors 1969-1970; “Sachlich, kritisch. optimistisch”; Eulenspiegel; Berlin 2010. [With apologies for my adaptation.]

We stop to gaze at the landmarks surrounding. Work on the Reichstag building has been recently carried out to seal it against the water damage that occurred in its desperate condition: torched by the Nazis, attacked in World War II, vandalized for souvenirs afterward. A symbol of the past attempts at parliamentary government in Germany? Or is it a symbol of a possible future?

Our French companion removes her right hand from Robert’s pocket where she has been warming it against the chill. The young woman gestures broadly, sweeping her hand across the panorama of ruin and division.

“I just want you to know,” Michèle responds to our questions, hesitantly at first in her charming French-accented English, then as clearly as if she were singing the Marseillaise. “The Germans tried to build a future for Europe their own way. They did it in 1871, they did it in 1914, did it in 1939. My father was a prisoner of war here in 1943, ordered to a camp near Berlin to build “Germania” – the world capital city that Hitler planned. Now, un siècle, a century of conflict, has passed and they have an opportunity to instead build that future arm-in-arm with other people.”

We kick the idea around as we walk through the Platz der Republik in front of the building. This was the Koenigsplatz before the abdication of the Kaiser. Will it change names again? We wonder.

Our guide doesn’t know. Robert speculates that this city will be reunited, but under which system? Today in the middle of 1971, in this place, we stand at a dividing point in history. Diplomats are tossing in their beds as we speak, wondering if the three-dimensional negotiations underway between the allied Four Powers, the Federal Republic of Germany, the German Democratic Republic, Poland and Czechoslovakia will finally end World War II and begin a new era.

Thousands of kilometers east of here, Soviet soldiers who our guide met earlier in his time in Berlin are patrolling the tense border with China. The occasional shots are fired. Everyone who cares knows that some sort of three-way game is being played between the Soviets, China and the United States.

Here, silent stones tossed about in the 1945 Battle of Berlin offer no opinion.

Bibliography:

Kegel, Fritz; U-Bahnen in Deutschland; Alba Buchverlag; Duesseldorf; 1971. On page 27, a network map shows the future U-Bahn lines on both sides of the Wall, to be developed as a single system.

Sarotte, M.E.; Dealing with the Devil – East Germany, Detente, & Ostpolitik; 1969-1973; The University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill; 2001.

It is bright enough now to read a newspaper. Our guide proposes a course along the S-Bahn viaducts and bridges back to awakening West Berlin. Another rubble field, site of the former Lehrter Bahnhof, is on our way. Robert and Michèle choose to remain behind for a few minutes.

We head away from the weighty stones and weighty questions toward awakening life in the big city. That is, our guide and we visitors head away. Looking back we see the young couple now lagging behind — two small living beings amidst the forlorn, inanimate stone pages of overburdened history. Even the Cold War, we realize, could find a place for a wartime romance.

Out of their earshot, our guide explains that people in sensitive assignments face difficulties in having normal relationships. It is not just the Warsaw Pact intelligence agencies prowling around, but also our own and those of our allies. This affects spouses, children and loves. Perhaps Michèle’s pre-school staff colleagues wondered who the strange men asking questions about her were. Perhaps Robert had to go to Brigade Headquarters and answer questions. Two years ago, two German women who were employees of RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) were questioned sharply about their movie double-date with an interracial pair of GI’s. Questioned so sharply that in fear they cut off contacts with the soldiers.

We continue along the Spree, the Soviet Zone of Berlin on one bank and the British zone on the other. The first morning S-Bahn train comes rumbling across the river from the Friedrichstrasse Station where it has met with the East division of the network. Passengers – those on good terms with the regime – transfer through the Berlin Wall, which runs through the station. At the Sandkrug Bridge, we pause to let Robert and Michèle catch up. This checkpoint is unfamiliar to American visitors preoccupied with Charlie. It is a crossing point for approved West Berliners. The border guards scan us from their tower.

They’re kissing!” someone whispers. Two figures blend into one as they embrace in warm defiance of the watching border guards. We watch silently for a minute, not as voyeurs at this distance, but rather like visitors in a museum who are drawn into the intricacy of a panoramic painting. The couple begins to walk toward the sleepy checkpoint for a closer look.

“Ils marchent bras dessus, bras dessous,” one of our group says. We give puzzled looks. “It’s a phrase that I learned in high school French. There is something about this place that leads to such disjointed thoughts.

“Hope is stronger than fear. Love is stronger than hate!”

One of our group whispers these words. No one asks why we are whispering.

We wait for a moment, wondering if they will want to catch up with us. But the sun has climbed over the monuments and the couple vanishes in a golden blaze that is hard on the eyes. Radiant beams paint our shadows long as we head back “downtown” for coffee.

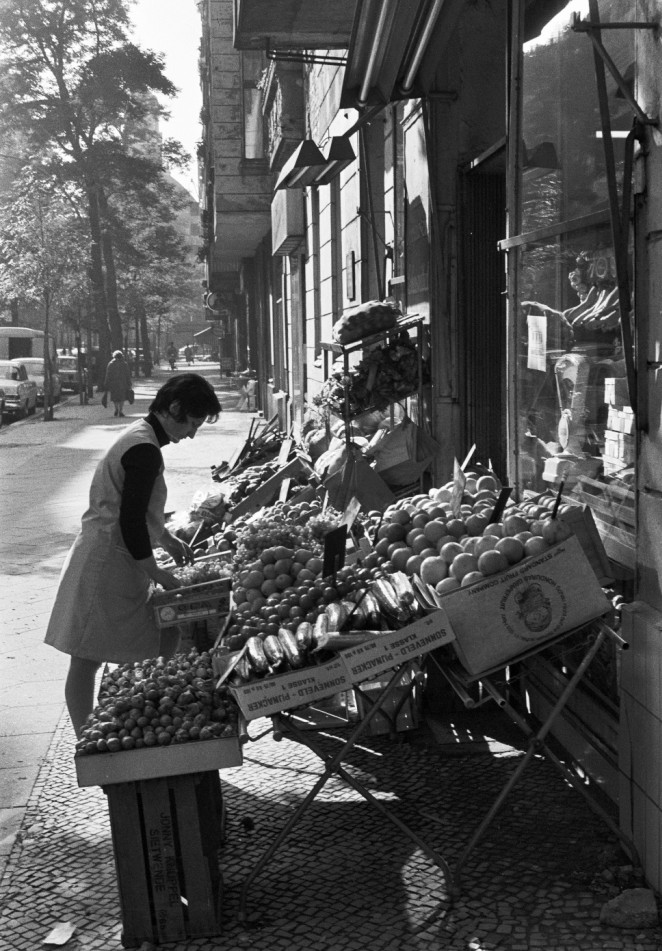

On our return, the day begins for Berliners. Milk is delivered; below, a Kreuzberg grocer lays out her attractive wares in the American sector.

For those who spent the night on duty, one more uneasy 23rd hour has passed safely. Soldiers, airmen, police and our little expedition have taken part in an experience that is our own.

We thank the people who shared this experience with us. Their actual names fictionalized or masked here are known but to God… and to the Ministry for State Security, and to the GRU, and to the Deuxième Bureau’s successor, and to 66th MI, and to the NSA, and to the BND and to….

Bibliography:Bavendamm, Gundula, editor; The Berlin Crisis and the Construction of the Wall; for the Allied Museum by Berlin Story Verlag; Berlin; 2011.

Quotes from:

Hamlyn Larousse Dictionary; Paris; 1984.

Westfall, Rev. Louise; benediction in Central Presbyterian Church; Denver; 2011.