by R. W. Rynerson, formerly SP5, Berlin Brigade

— Thu 21-Nov-91

As the Cold War just fades away, the scholars who spent a generation trying to figure out how and why it began are turning their attention to the question of how and why it ended. They will not find the answer in documents. There is no paper trail into the hearts of the people who long stood watch on both sides of the barbed wire. Each of us who were there, however, can tell you the moment when the end began– the moment when someone let their humanity slip through.

The world was watching the heavens, when I saw the Cold War begin to melt. On that day, July 20th, 1969, Americans landed on the moon. If we wanted to talk about something here on Earth, there was always the war in Vietnam. For a little group of us, however, that night was supposed to be business as usual.

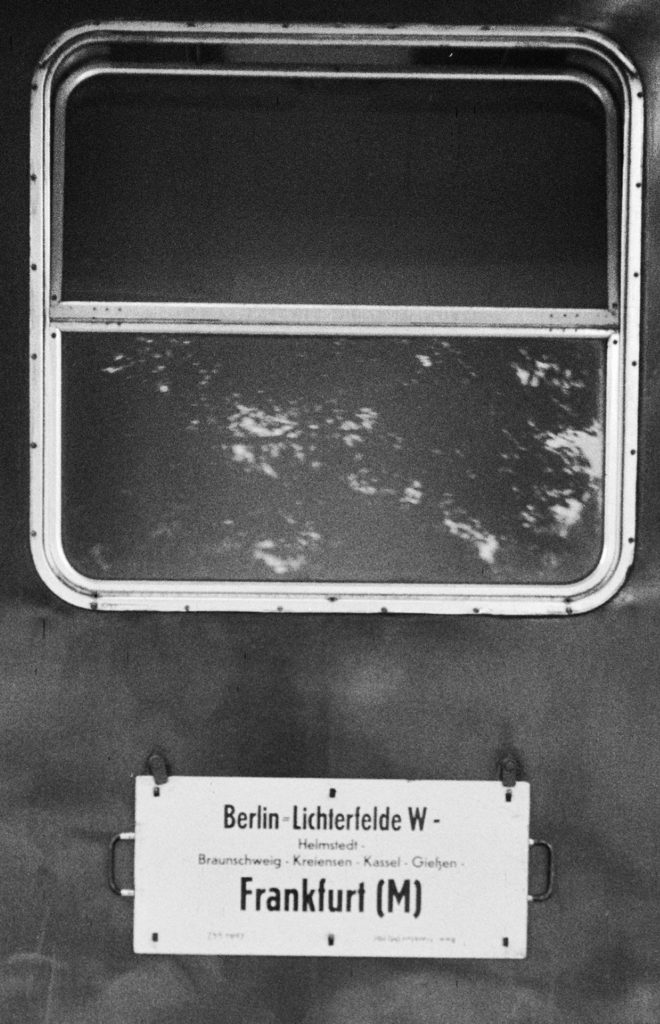

We were in the crew compartment of the U.S. Army’s Military Train from Berlin. It was 8:30 in the evening, Central European Time, and Dm80610 as it was known to the German and American railwaymen, was rumbling over the switches out of our little station, picking its way toward the one remaining main line open to the West. After a stop at the West Berlin Wannsee station, we would roll over 100 miles through East Germany.

The East Bloc called it the German Democratic Republic; we called it the “Soviet Zone of Germany” and we would report to the Soviet Army checkpoint officers, who would review and stamp the paperwork of every passenger.

Out of an old German leather attache’ case came the stack of military I.D. cards, passports, and multi-colored, trilingual documents in the languages of the four Occupying Powers. In a few minutes we would be out of the American Sector of Berlin, time enough to put someone off the train if all was not in order. Mr. Pachurka, a civilian interpreter for the U.S. Army who had spent too many years on the knife edge of border conflicts, gave each photo a sharp glance.

“An Irish passport?” he growled. As the GI On-the-Job-Trainee interpreter, I had been laying out the accumulated identity material, and had opened the unfamiliar booklet to the picture of a lovely Irish woman in her early 30’s. All work stopped. Anything out of the ordinary could trigger suspicion by the Soviet checkpoint officer. Quickly, I explained to the narrow-eyed Pachurka and to our Train Commander what I had learned a few days earlier in the Berlin Rail Transportation Office: this passenger was traveling with her mother and young brother on papers issued by her employer, the British Embassy in Bonn. They were on holiday, a vacation that a secretary could afford, on military standby travel.

Wheels turned in Pachurka’s head. He paused and then advanced a hypothesis.

“She is actually with British Intelligence. The Irish hate the British, but she had a son out of wedlock, and had to find a job that would take her away from home forever. This woman,” he fished out another Irish passport, “is truly her mother. But this boy,” and he held up a third passport, “is actually her son, not her brother.”

The Train Commander and I stared at each other for a long moment, while the train wheels clicked over the bumpy Reichsbahn track panels underneath us. Now that they had been pigeon-holed, our Irish guests were welcome to be on Dm80610, as it passed into the Soviet Zone.

In northern twilight, many passengers stayed awake on any trip. That night, Mary and her mother and her “son” were listening to the moon landing on portable radios. The signal traveled for thousands of miles, and then hit the East German jamming program, a powerful station which operated on the fringe of the Armed Forces Radio Berlin frequency, so that the space message faded painfully in and out. I joined them for awhile during the lull between work projects, keeping Mr. Pachurka’s cynical observation buried in my heart.

At the Marienborn border checkpoint it was a special night. We took the Soviets’ salutes with undisguised grins on our faces. Their officers allowed themselves to be sportsmanlike, congratulating us on our space success, joking about when we would be working at a checkpoint on the moon. On the edges of this scene, the Russian and Asiatic enlisted men remained stone-faced and cautiously alert, as on almost every night. For twenty years they and their fathers had watched silently, while their officers smoked American cigarettes, okayed our train movements with American ballpoint pens, and (usually) waved us on our way.

Back on the train, I found the Irish family looking out at the spotlit border station. German railway workers busily serviced our train. Border police walked along it with their German Shepherds and the wheeled mirror, checking the undercarriage for refugee riders. A Russian soldier stood watching this scene from the platform, his face locked inscrutably.

Mary, the Irish employee of the British, had dutifully read the six pages of rules on travel to and within Berlin. She repeated some of them back to me.

“But there’s no rule that says we can’t smile, is there?” she said, adopting a leprechaun voice. At 11:59 p.m. of July 20th, 1969, the Cold War began to melt, as Mary turned on a wider and wider Irish smile.

The Soviet soldier tried to maintain his composure, but he could not. His lips began to quiver, a silly grin crossed his face, and then finally he beamed a smile of sheer enjoyment. He lost his military bearing, and was only saved from complete collapse by our conductor’s signal. The train started, and he faded from view.

I walked back along the long corridors of the sleepers to the crew car on the end of the train. I always enjoyed those moments, as our sleeping passengers crossed the deadly border behind the closed doors of their compartments. Intense spotlights probed the corridor windows for a moment, and then I felt the surge of acceleration as we hit the smooth track of the Bundesbahn and West Germany.

That night, Mary’s smile seemed like an amusing incident. But as memories of other details fade, it has stuck in my mind. How far in space and time did that smile travel? Pachurka, the cynic, would not have extended his improbable hypothesis to imagine a Russian soldier taking that warm glow home. Still, Mary’s smile was a step in the right direction. And if Pachurka was right, from a woman whose own life was being lived in exile from her small country. # # #

Postscript:

It is interesting how things come along later in life to fill in details. In the Denver Post of December 26, 1999, page 5F, Irish film director Pat O’Connor, who grew up in Waterford, Ireland in the period when Mary was a girl there, stated that:

“Very cruel things happened to people in their quiet lives. If a woman got pregnant, she was sent away, and the nuns kept the child. She had no voice.”

The soldier crew of Dm80610 could not imagine that world, any more than we could imagine the hard world in which Mr. Pachurka had survived.

– rwr –

Robert Rynerson was sent to West Berlin in 1969 by the U.S. Army, to serve as a Russian-English Interpreter in the Rail Transportation Office, after having been trained to be a Personnel Management Specialist. Staff shortages resulting from the Vietnam War led to his assignment as an on-the-job-trainee Russian-English interpreter, relying on his high school Russian and two years of college Russian. The Berlin Military Trains were discontinued in December, 1990, after generating four decades’ worth of equally improbable sounding stories. ‘Frank’ Pachurka was the interpreter on the last train.