“The moon makes everything yet more odd.”

- Alfred Lichtenstein, Romantisches Fahrt, August 1914

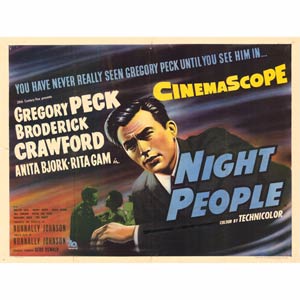

Alfred Lichtenstein, Berlin poet of the Cafe’ des Westens circle, penned that observation on his way to the Front in World War I. He would have noticed the purple cast of fluorescent lighting or the yellow of streetlights in the Berlin of 1969-71, had he survived the Great War. Soldiers of the Allied forces in Berlin worked around the clock in an atmosphere best captured by the Hollywood production Night People. Critics have found that the film has a plot that makes little sense, but it gives the edgy feel of the Divided City at night.

For some Americans the night’s work began when the two Duty Trains pulled out of the Rail Transportation Office yard at Lichterfelde-West. As soldiers and dependents headed for bed in Berlin, trains were rolling into the night. Air traffic control, under Four Power supervision, was guiding the last Pan American, British European Airways, and Air France flights into Tempelhof Flughafen. G-2 Division and Military Police patrols were peering into the darkness. And at the gates of Andrews Barracks, McNair Barracks, and other facilities, the most ancient duty of soldiers was covered by guard mounts from the units stationed there, along with the Berliners in U.S. uniforms of the 6941st Labor Service Battalion.

When I started to put thoughts of my time in Berlin on paper, it was hard not to remember the nights. There were good nights and there were bad nights, of course, but perhaps it was the combination of being in a big 24-hour city and the military necessities that make memories hard to shake.

How to present this big subject? May I narrow this topic down? Night falls on Berlin in the usual order, from East to West, but it is easy to veer into cheap symbolism regarding East Germany. Millions of Berliners were busy sleeping during these hours, and the ones who were not have their own writers. This then is just one view, a journey organized from West to East, overnight across the fitfully-sleeping Weltstadt Berlin, as seen from an unmarked U.S. Army sedan.

The names and events of the evening, of course, are fictitious, as are the remarks of individuals “quoted” in this story. However, readers who were in Berlin at the time should find a feeling of familiarity with the people and situations described in the following words and pictures.

Another way to narrow this down is to pick a night in the tense summer of 1971. International negotiations grinding toward a climax would ease the tension — if successful. At 52 degrees North latitude, the same as Edmonton, Alberta, the midsummer night in Berlin is short and usually comfortable. No need to dwell on memories of pushing cars out of snowbanks on the long winter nights, nights when the Cold War really was cold.

— by R. W. Rynerson

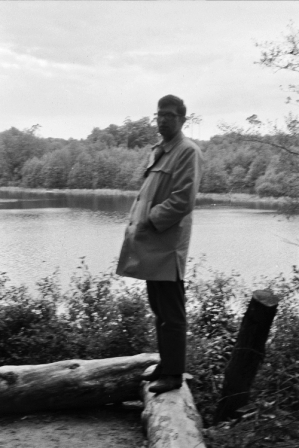

We take a cab out to the end of my world, the Havel. Half lake and half river, in the Southwest corner of Berlin, the Berlin Wall in marine marker buoys runs down the middle of it. This has created such a cul-de-sac that we pass only a few late-evening gasthaus customers returning from beer gardens where the warm social glow was interrupted when persistent yellow jackets drowned in their beer.

Our cabbie is a bit nervous heading down into the forest with two foreigners this late at night. He can’t understand why we aren’t headed for the Ku’damm “downtown” like any sensible visitor would be. On this summer evening, night will pass quickly, he comments.

We are meeting our ride at the controlpoint at the end of the Glienicke Bridge, our end that is. On the other end of the Freedom Bridge, as Americans called it, is Potsdam, in the Soviet Zone of Germany, or East Germany, or the German Democratic Republic. Most media coverage is fixated on Checkpoint Charlie, handy to the old seat of government and to the newsrooms and wire service bureaus. Out here it is lonely, surrounded by park land, with a police controlpoint and not much else. A few famous moments of the Cold War, such as the exchange of U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers and the Soviet spy, Colonel Rudolf Abel, have taken place here, but many Americans, including journalists, are not sure where “here” is, because it seems so much easier to think of East Germany as being east of West Berlin.

2015 – Steven Spielberg release Bridge of Spies takes a Hollywood – Babelsberg look at the Glienicke Bridge.

It is so quiet here that we can hear the water of the Glienicke Lake swishing back and forth into the Havel under this bridge. As we peer west into the dark GDR, trying to see past the brilliantly lit border area, we hear the distant sound of one vehicle coming up very fast. Turn back to look east, into the American Sector of West Berlin. Far up the broad lanes of Koenigstrasse, we can see two sets of headlights. The ordinary light of one set is drowned in the intense light of the other coming up from behind. The lights of the lead car swerve askew as the driver pulls crazily clear of the onrushing auto behind. We see the intense lights cant as the speeding second car takes the lead, then cant back unnecessarily on this wide street; the speeder asserts his dominance by cutting off the only other vehicle on the road, arriving first at the controlpoint with a lead of a minute.

The supercharged vehicle is a Soviet Military Liaison Mission car. Just as the three Western allies have specific rights to tour the Soviet Sector of Berlin and the Soviet Zone of Germany, so the Soviet Union has parallel rights in the areas occupied after World War II by Britain, France and the United States.

With unrestricted right to pass through the lines a key point of our legal position in Berlin, the Soviet soldiers are waved through. We do not know why they were speeding, nor why they were driving on a city street with their headlights switched to “bright.” In this quiet hour, it is easy to start speculating.

The second car turns out to be our ride. A young American in an open white collared shirt and tan slacks, his sideburns too long — in the 1970 style — driving a worn Taunus 20M, a German Ford, with Berlin civilian plates. The car is painted black and looks like a second-hand Berlin taxi, but instead is a second-hand U.S. Army Military Police car. Fully worn out by the MPs, its engine gunked up from idling for hours of driving slowly through the military housing areas, it risks stalling from vapor locks in hot weather, and its automatic transmission shifts at surprising times. Now it is disguised with a single coat of black paint. When scratched, it bleeds a glossy olive green, and there are four doped-in screw holes in the roof where the blue “bubble gum” flashing light used to be installed.

It also declares itself to be an unmarked car by the lack of junk in the back seat. It is too clean. The only article on the front seat is a dog-eared copy of the cleverly folding Falkplan — Stadtplan Berlin. It is “…patentgefaltet…” On the back seat is a folded windbreaker. The last hour of the night, our guide says, will be chilly. The darkest hour truly is before the dawn, and yes, still is the watch the ends the night. These old truisms apply to soldiers in plainclothes as much as in uniform.

With the personnel shortages created by the Vietnam War, our guide is in an intelligence unit that is entirely expendable — one term enlistees and draftees, untrained for intelligence work and learning on-the-job. The unit is drawn from personnel assigned TDY (Temporary Duty, or “seconded” in British and Canadian military terminology). Berlin in its special situation has many peculiar organizations of this type, on all sides. The bright lights of the controlpoint make it hard to see the divided waters of the Havel. We drive north a little way along the shoreline. The woods of the Berliner Forest Dueppel lay still behind us, the only sign of life the reflecting stare of a tiny deer caught in our headlights.

Our driver goes around to the back of the car and pulls a big set of binoculars from the trunk. Passing them back and forth, we orient ourselves in the magnified world of the lenses. Yes, there is the line of buoys bobbing up and down in the lake. That is the Berlin Wall, looking as innocent as a fishing net on the surface. Behind it is the shoreline. In some places, the shoreline is an extension of the Wall; in others there are luxury villas of the pre-World War II Berlin suburbs. A handsome, wooden sailboat is tied up in front of one waterfront property. Someone is turning off the garden lights and stacking up the chairs from a gemuetlich evening. We can think of the possibility of a long, midnight swim that would bring a person up onto the shore upon which we stand.

We wait for a few minutes, enjoying the comfortable world of Berliners, a world rudely interrupted by the Twentieth Century, and then there is a stir on the water’s surface.

A GDR patrol boat — the U.S. Army identification manual says it is copied from American World War II PT boats (Patrol Torpedo) of the Pacific War — glides shark like, low in the water toward our vantage point. Its twin engines rumble. Twin spotlights dart in all directions. Twin machine-guns are manned. These, we learn, replaced the old patrol boats that had only one engine, one searchlight and one machine gun. Their prey, however remained the same. The hypothetical swimmer would be fished out of the Havel dead or alive. The boat-owning cousin from West Berlin who might think of maneuvering up to the buoys for a late-night escape rendezvous with East Germans would be detected by this crew, and would know that the bullets would not stop at the watery boundary line.

Sinister with the low notes of its passing, the shark analogy is completed when its crew spots a flare hissing up into the sky. Out of sight around a wooded peninsula, border guards on the GDR shore have fired a signal for assistance. Perhaps in the morning we can come back and see the dead rabbit that they gunned down in their panicky hunt for a refugee, but for now, it’s real. The radio squawks, and the engines rev up. Crewmen grab for their balance as the “shark” reverses course and heels over in the process. We watch it hydroplane up out of the water as it speeds toward its prey– then take a deep breath. We had forgotten to breath.

“Pray for the rabbit, pray that it IS a rabbit,” whispers our guide.

The Cold War influenced Berlin nights in some peculiar ways. As our guide navigates the Taunus through the numerous jogs that bring us to new views of the harshly-lit Wall and its effects on neighborhoods, we find ourselves on a dark stretch of landstrasse through farmers’ fields. The glow of city lights is diluted by distance; there is no other traffic on the road. By daylight on the way out to the Havel (as shown in the photo below), this drive on the narrow, stone-paved road was fun. By night, our driver points out that the lack of shoulders and the nearby trees make a dangerous combination.

And then a little yellow glow appears from the distant smudge of tree line. It grows larger, and now red barrier lights are flashing ahead. We stop at the gate that has dropped across the road and our headlights illuminate the flame red and dirty cream colors of a stunted S-Bahn train – only two cars long. The electric blue flash of third-rail shoes lifting off the interrupted trackside power source punctuates its passage. Pale incandescent lights, wired in series from the 800 volt traction power, blink on and off for the moment in which the Dueppel – Zehlendorf shuttle coasts over the road crossing. A lone passenger peers out into the darkness. The gate rises, the red lights dim out, peace is restored.

The Dueppel line, our guide explains, is a political vestige of grander times. This is a piece of the original Prussian railway from Berlin to Potsdam. It was bypassed by newer routes, but once carried the grandest names of the newly united German nation. In the years before World War II, it carried steam-powered S-Bahn express trains. Now on this night, it goes through the motions: a five-minute run from Zehlendorf, where it connects with the big S-Bahn trains to the city center, a four-minute layover, then a five-minute run back to the crumbling shack at the end of the track in Dueppel. Every twenty minutes, seven days a week, this sorry leftover trundles “hin-und-zuruck” — to and fro. On Saturday nights, it continues hourly through the owl period, sitting patiently in “downtown” Dueppel, for example from 2:19 a.m. till 2:54 a.m. It might be quiet enough out here, according to our guide, to hear the swamp creatures moving out of Krummes Fenn.

For a quiet moment on our tour, we are far from the cares of world politics and the divided city. And then, having reached its terminal at the Berlin Wall, the shuttle train comes rocking back towards us, flash-lighting the countryside with its third-rail shoes’ arcs. When the gates go up again, we are on our way.

Our meander through the Berlin night continues. The tree canopy over Zehlendorf streets that was ravaged in the Second World War’s aftermath and in the Blockade years is starting to recover. In the dark the tree-lined streets can be disorienting. Our driver knows the way– slowly we cruise by some of the landmarks not usually on tourist itineraries– the pension in which the CIA and European intellectuals formed an agreement for American funds to subsidize a magazine of non-Communist liberal political opinion, houses occupied by various unidentified government organizations, consulates, and the homes of famous 20th Century German figures.

With few people on the streets, it is easy for us to imagine the former Reichsfinanzminister, brilliant German banker Hjalmer Horace Greeley Schacht, arriving late at his villa after his dismissal from his last post by the Nazis who he had earlier helped to power. The “Bankers’ Express” S-Bahn trains were still making the fast run from Zehlendorf to the city center at 120 km/h, but that and the rest of Berlin’s infrastructure was living on borrowed time when Schacht went home from the office after a series of demotions into that January 1943 Zehlendorf night. Schacht was engaged in conspiracies against Hitler. Several of the interlocking circles of the Widerstand, the anti-Nazi resistance, crossed paths in this far corner of the capital.

On another street in this district of villas, his successor — the affable war criminal Walther Funk — might have been staying up late, too. Known to pre-war Western journalists as one of the few Nazis who could crack a joke, Funk had been a business news journalist himself. Keeping his job amidst the plots and counterplots in Third Reich governing circles when his personal life was so notorious took its toll on this alcoholic. Funk left the neighborhood to live in a mansion in nearby Schlachtensee, bought at a fire sale price from its Jewish owners. Funk left that property in 1945 for an appointment with the judges at Nuremberg.

Now our guide on this evening is one of the residents of Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11, which the U.S. Army moved into after a Soviet general was moved out of it in the summer of 1945. Since the inglorious end of the Nazi era, the villa has served a variety of purposes. Its tennis courts, now covered by an office building, served as a post-war recreation facility. [Note: the office building was removed later by the German federal government. The street address of the villa has been changed.] Refugees of interest to the Allied governments were housed here at various times. And now, GI’s with miscellaneous non-conforming jobs, such as the Commanding General’s enlisted aide, live in rooms carved out of once grander rooms. A brick barbeque has been built in the secluded, walled garden and the Americans who live here invite their British, French and German colleagues over for an American steak with German beer.

For more of the Zehlendorf story: https://www.berlin1969.com/stories-geschichte/sven-hedin-strasse-11/

Dittfurth, Udo and Braun, Dr. Michael; Die elektrische Wannseebahn – Zeitreisen mit der Berliner S-Bahn durch Schoeneberg, Steglitz und Zehlendorf; Verlag GVE; Berlin; 2004; ISBN 3-89218-085-7.

Niemoeller, Martin; God is My Fuehrer; Philosophical Library and Alliance Book Corporation; New York; 1941; preface by Thomas Mann.

=================================================

It is just a short drive from his home to the Krumme Lanke U-Bahn station, known as “Crummy Lake” to some GI’s. Trains from the Wittenbergplatz heart of the West Berlin U-Bahn lines are gliding into the station. A dribble of passengers disperses into the diverging streets. We’ll return later to meet our contact for a ride “downtown” — but there is more to see around each dimly lit corner.

We stop for a few minutes in the shadows of the Dahlem Church yard, the tombstones labeled with the titles of the scholars and officials who populated this parish. While it is amusing for a moment to reflect on the fact that Germans took their titles to the grave with them, the shadows here include the memory of Pastor Martin Niemoeller, vicar of Berlin-Dahlem, former World War I U-Boot Kapitan, and a man who took the responsibility to preach the Gospel as a duty, carried out in spite of the Gestapo. He was tried by a People’s Court that could find no violation of law in his preaching, but the Gestapo took him from the back door of the courthouse and imprisoned him. The shadows here also include the unidentified young men who sat taking notes in his church, their hostile body language meant to intimidate, trying to find something in his words that would convict him, young men for whom he prayed.

A few streets away, we cruise past the street associated with the CIA in Berlin, tiny Foehrenweg. Our guide turns taciturn and suddenly reminds us that summer college students in North America are playing Frisbee on campus lawns right now after class. Someone is turning the pages of their Twentieth Century History text. Here, in this so quiet corner of Berlin, Twentieth Century History is not the title of a university course. Two-thirds of the way through this bloody century, someone on the streets we travel now is making history.

A light in a window flashes on and then off in a mansion. A millionaire getting up to take an antacid? A tired intelligence officer brushing his teeth in a bathroom that was last redecorated by its owner in 1935– an owner who left suddenly in 1945? Or a diplomat coming home from an evening social event? There are no answers in our night survey. Nights in Berlin seem to be full of more questions than answers. Our driver is turning the car toward the U.S. Headquarters on Clayallee, where we will visit the Americans who stand guard through these restless nights.

================================================

Read more in these books (if you can find them):

Oldfield, Col. Barney, USA; Never a Shot Fired In Anger; Duell, Sloan and Pearce; 1956. . Col. Oldfield set up the U. S. Army’s press center in the villa at Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 that he was told had belonged to Nazi Walther Funk. He first had to talk Soviet soldiers into leaving it.

Stockton, Bayard; Flawed Patriot: The Rise and Fall of CIA Legend Bill Harvey; “Lights blazed in the high-gabled redbrick building rising from a cleft in the wooded Berlin suburb of Dahlem, facing on what was now called Clay Allee. The real entrance was on an obscure, parallel dead-end street…”

Schwartz, Harold; Outpost Berlin: Cold War 1961-1964; Trafford Publishing; 2010. (Available in 2020 via Barnes & Noble Nook.) “Capturing the essence of the era, Outpost Berlin: Cold War 1961-1964 presents a historical look at the stories of American military intelligence officers, German escapees, and the escape helpers.

“Outpost Berlin chronicles the tales of both successful and failed escape attempts over the Berlin Wall since its erection in 1961. Each chapter begins with a short historical background and description of the location, a dedication to an American or German who played a significant role in the defense of West Berlin, and a prologue detailing the implications that the incidents had for West Berlin’s future.”

Counter-intelligence Special Operations A 1969 U.S. Army training film shows how to investigate an espionage operation. The concepts may be familiar to viewers of televised thrillers, but the special treat is that the film was shot in the U.S. sector of Berlin, showing actual military facilities and procedures, climaxing with a film noir night raid on the villa at Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11. 36 minutes of nostalgia: former U.S. Army Spec 5 Susan Rynerson in reviewing the film notes perceptively that “the good guys wear London Fog.”

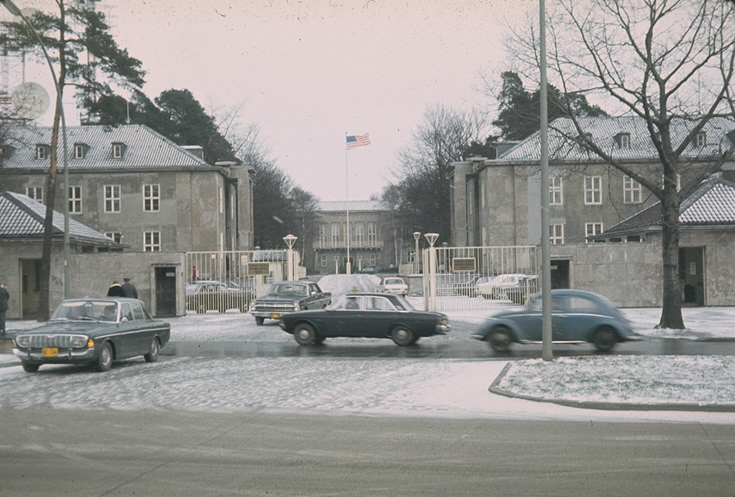

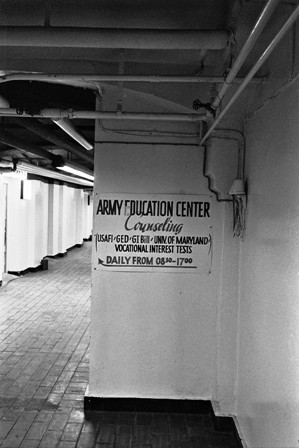

The focal point of U.S. activities in Berlin was the headquarters building on Clay Allee at the corner of Saargemuender Strasse, diagonally across from the Oskar-Helene Heim U-Bahn Station. It was the former Luftgau Building, the air defense headquarters for the eastern region of Germany. When American troops entered the city on July 4, 1945, it had been gutted.

Our guide wheels the black Taunus into a side street across Saargemuender Strasse from the gray walls of the headquarters compound. With its Berlin civilian plates, and its “unmarked” look, it cannot be brought into the main parking area in front. Of course, because this phenomenon is well-known, our driver admits, it is likely that one or more East bloc intelligence agencies watches to see which cars are parked nearby. However, it seems that a peculiarity of this city is that intelligence activities are mainly covered by their large numbers and a certain low-key nature, rather than by being completely secret.

We are admitted through a side gate and zig-zag through the seemingly empty complex toward what some might call the “brain” of the multi-talented alien presence that Berliners found on their doorstep 25 years earlier.

“Perhaps that’s the wrong metaphor,” our guide suggests. “I think that it’s more the heart.” This is puzzling, but there is no time to think about that, because we are approaching a steel cage entryway and then waved through by a guard. Down winding stairs, into a space recognizable from World War II movies as the interior of a German bunker. However, this is now the location of the Emergency Operations Center, the “EOC” as it is known to the military. A variety of functions can be carried out here, but tonight it is quiet.

It is not empty, however. Someone is always on duty here, as the Army sleeps with one eye open. In the Signal area, the Duty Train radio messages are coming in. As the train passes each station, the radio operator reports its locations with a field radio. On the global scale, an unreliable tropo-scatter radio link bounces signals over the heads of the Soviets and East Germans to West Germany. When the Troposphere does not cooperate, the signals go to who-knows-where. There is supposed to be a Signal Corps officer in charge of this, but the Vietnam War is underway, and this sensitive operation backed up by four trucks and a lot of expensive equipment is supervised by a Spec 5. The Signal technician started work at midnight and will be on duty for 72 hours, then off for 24 hours. He will often be working alone.

“There’s the Alert board” — it’s the first thing we notice as we walk into the Operations area. Each unit is labeled on the board, with a set of lights that indicate what percentage of readiness the unit has reached in an alert. When alerts are held, whether for training or for real — the distinction is blurred in Berlin by the situation in the Divided City — anxious NCO’s and officers watch the pattern of lights and look repeatedly at the clock as calls come in as if on election night. Unoccupied steel desks wait for the fingers that will drum impatiently on their dark, rubberized surface. A silent manual typewriter sits surrounded by sheets of the Army’s odd-sized paper and carbon sheets. A worn Berlin Brigade telephone directory sits squarely in place on an otherwise empty desk, a pencil and a blank notepad positioned precisely next to the directory.

Here is the heart. It is a desk manned by a sergeant who welcomes us with coffee in his quiet Operations center. The man has a gruff demeanor, but at the moment has all the time in the world to chat about Berlin. This is his second tour in Berlin. He was here as a young infantryman on his first experience. In the meantime, he’s served in swamps called U.S. Army Training Centers in the South, and he’s been to Vietnam. He likes to tell stories about the Ku’damm bars and the women back when he was a bachelor, in what is now called the “Wild West days” of pre-Wall 1961 Berlin.

But as we chat, we realize that this is a kind of cover, a way of turning the subject away from something serious. The flash and glamor is not what brought him back for another round of dealing with dark winter days, international politics at the barrel of a gun, and rules, rules, rules. What brought him back is the opportunity to do something meaningful with his life.

Perhaps the Warsaw Pact generals do not know which sergeant is on duty tonight. Our guide explains that we tend to take for granted that they can have that information. What we hope is that they know that no matter what happens, this man will not be fazed by it. If it’s a shooting at the Wall, he’ll call the right people. If a gate guard spots someone suspicious taking photos, he’ll alert someone who’ll go and take a look. And, he is one of the people who has to think about the unthinkable. The Warsaw Pact’s plan for the “liberation” of West Berlin calls for massive air attacks on the Allied Military installations as the first phase of a rapid project designed to be over before the West could react. Unless everything they planned were to go perfectly from the start, the veterans of the Great Patriotic War who head the Soviet military know that this sergeant will make the phone calls that start World War III.

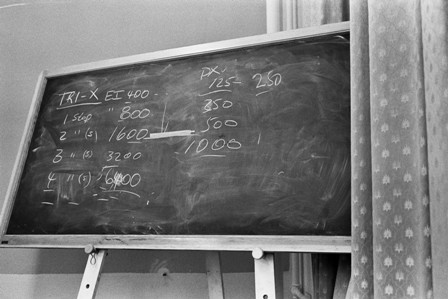

In the night, a classroom chalkboard in the Brigade HQ waits for tomorrow morning’s photography class.

Bibliography:

Beringt, Henrik; Outpost Berlin; edition q, inc.; Carol Stream, Illinois, 1995.

We climb back up to the steel cage at the top of the stairs and walk back along the empty halls to the street. A guard salutes us and we are out into the warm Berlin summer night again. Did we leave anything in the car? Our guide explains that the unmarked car is going to stay here in the parking lot. We are headed into the British sector and so the next part of the trip will be unofficial.

We stroll along Saargemuender Strasse to the Oskar-Helene-Heim U-Bahnhof. A sleepy ticket agent is still on duty — the last trains will depart in an hour. Our guide has a Monatskarte monthly pass, but we must pay 40 pfennigs each for an “einfahrt” single trip ticket. It converts to ten cents on the U.S. dollar exchange.

On the platform there are a handful of subdued passengers waiting, along with a couple down to see their friends off after an evening social event at their home. The station is in an open cut, deep enough that street sounds are faint. Before our guide has finished explaining that we will meet a friend who will drive us downtown in his POV (privately owned vehicle), the train presents itself in a rush of yellow paint and bright lights.

[For a 1971 daylight visit to these U-Bahn stations and a glimpse of the Linie 53 bus, visit the You Tube clip posted at:

https://youtu.be/8Z6kKReXJDE .]

A few passengers alight as we board. There are a few more still riding to the last two stops. Our attention — and the attention of everyone in the car — is drawn to a drunk stretched out lengthwise on the longitudinal cushioned bench. This seating is meant to have passengers facing the center aisle, but this customer is facing toward the ceiling. Not that he can see it, because he is sound asleep and SNORING. This is what has broken the ice among the rest of the passengers. They nod in amusement toward each other and wonder what is going to happen at the end of the line. Usually– if not reading– they would sit and earnestly study the wood grain pattern panels in these pre-World War II cars. Now they are a group of amused and concerned citizens.

Next stop, Onkel Toms Huette, the U-Bahnhof in the middle of a neighborhood shopping center. The lights in this indoor station flicker on the drunk’s face as the train slides up to the platform. He doesn’t move.

A customer whose stop this is walks over to the train starter who is ensconced in his elevated booth and says something to him. The doors slam shut, latches clicking, and as we look back the starter is calling someone on his phone. The drunk is two minutes away from meeting his fate.

The small subway car rocks and rolls over the switches at the Krumme Lanke terminal, lights flashing on and off as the third-rail shoe jumps from one track to the other. Our sleeping car passenger shifts slightly, but is not disturbed.

The other passengers head quickly toward the exit, perhaps to see if the Linie 53 bus is still running, or perhaps to avoid finding out what happens next to the drunk. We linger, being Americans who are curious about everything, and become witnesses to the effective BVG (Berlin transit system) method of dealing with this problem.

A rail division supervisor and two big guys in coveralls emerge from the shop facility, climb onto the platform and walk along the train, peering into the windows of each car. It is not difficult to find the sleeper — if they did not see him they would hear his snores in the quiet train.

We’re concerned. Drunks have a nasty habit of taking a swing at someone who disturbs their sleep. These BVG men, however, seem to have the drill down perfectly. The supervisor tells the drunk to get up. He doesn’t.

The supervisor gently pokes the drunk. He tries to snuggle down more comfortably on the bench seat. The supervisor nods to the two big guys from the shop.

Each of the shop men grabs an end of the drunk – one grabbing his arms, the other his feet. For a moment, we wonder if they are going to try to put him on his feet, something that would be awkward and risk him swinging at them.

But they have practice. With perfect timing, in a sort of beefy ballet, they swing him off the bench and then let go.

Ooooffff! The drunk crashes to the floor of the car. Angry and wide awake now, he struggles to his feet, ready to take that vicious swing at someone. Continuing the ballet, however, the supervisor steps back and the two shop men grab the drunk, one on each side, and march him up the stairs to Argentinische Allee. His feet only occasionally touch stairs, mostly the shop men are carrying him as we follow at a safe distance behind.

He is propelled out onto the street by this method, and the supervisor swings the door shut behind us and stands there with his arms folded. The drunk is on his own now. Cursing and staggering, he tries to figure out where he is. Suburban-feeling Argentinische Allee is not a place to find a cab at this time of night, and as we walk briskly away from him on our own mission, it is difficult not to worry on his behalf. On the other hand…

While our friend gives us a ride “downtown” to the Ku’damm night life, other Americans are awake, too. In the barracks, in the Army Security Agency’s electronic watchtower on the Teufelsberg, in the Allied Air Traffic Control Center, in tiny exclave Steinstuecken, and at places yet unknown to the public, Americans and their allies were on duty.

Our guide can describe the scene in Andrews Barracks, former home of the SS Hitler Leibstandart unit and now the home of units which are just about the complete opposite of that organization. Andrews is the home of Special Troops, the battalion formed of support units which carry out the “blue collar” and “white collar” jobs of the Army. In addition, the Army Security Agency’s soldiers live here and the blatantly anonymous Detachment A comes and goes on their mysterious missions.

At times, the people here — according to our informed guide — get the feeling that they are on a Midwestern college campus. At night, though, the watchfulness that characterizes military life in Berlin continues. Each unit has someone awake at all times; each unit has people who work strange hours and are coming home late or getting up early.

Some, like the conspicuously fit guys with the Germanic and Central European visages of Detachment A inspire curiosity that must be contained. We pass them, according to our guide, with a nod at most. Others, such as the Brigade’s early-rising pastry cook, inspire a desire to get to know him better. He will come home in afternoon to the barracks with tasty samples of his work. Each man has his place, but when he comes “home” to Andrews, he’s looking for the little bit of America that is open all night.

Sometimes, before heading out for a late night beer or brat, it is necessary to do Army things. Our guide on this night tells us about the ironically named “G.I. Party” that is held on the Friday night before a Saturday inspection.

In the photo below, the editor of the Berlin Observer, the Berlin Command’s newspaper, formerly a staffer for an American television network, shows that he is ready for action in one of those memorable military moments in the draftee Army.

This photo was taken just after an angry sergeant had told his collegiate enlisted men that this shower room and latrine area was not clean enough, because they had not “removed that grey stuff sticking out between the tiles.” Informed by his troops that this was grout, and that removing it was ill-advised, he simply made his order more emphatic.

Invoking the Nuremberg defense, that they were “only following orders,” the clerks, editors, art specialists, public relations staffers of USCOB, U.S. Command Berlin, used their Army-issue putty knives to strip off the grout. About two weeks later, members of Detachment A, located below this shower room, came storming up the stairs demanding to know why the ceiling of their shower room was collapsing from the effects of water dripping from above. Puzzled German workmen from the Facilities unit of the Engineers moved in to clean up the damage and restore the grout.

In photos below, the stark corridors of Andrews Barracks are silent, except for the eternal military sounds of soldiers grouped around a musical instrument in one of the rooms. The sound files which should load from this page were recorded “live” on a cassette machine in a room of the USCOB Billets in September 1969, with the voices of SP4 John Armstrong on the guitar, and “Fitz” and “Robert” briefly offering helpful, unneeded advice.

Technicians and clerks who keep the red tape moving for U.S. Command Berlin are sound asleep now, perhaps dreaming of their college days. In 1968, when the U.S. government ended draft deferments for graduate school students, the Army suddenly ended up with a plethora of college graduates.

This was a mixed blessing for the Army, which gained people who could step into office jobs with little training, but who also had little respect for the idea of a military career. Still, they got the job done, and no one who had seen the Berlin Wall had to ask why.

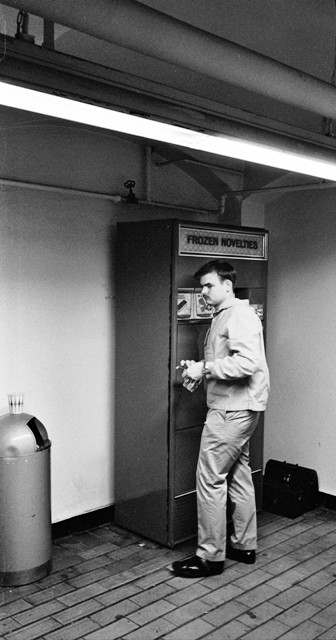

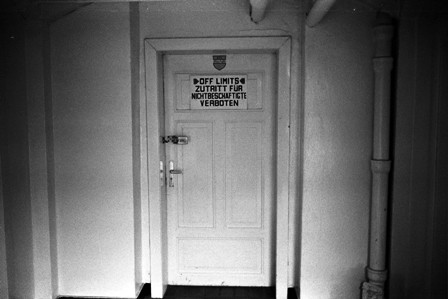

The basements of Andrews Barracks are as full of oddities as are the upper floors. The “Off Limits – Verboten” room may be the PX system’s secret stash for Playboy magazines or it could be the cover for an intelligence organization’s storeroom. An amazing variety of services are offered to soldiers. At night, these hallways are mostly silent. But someone is awake– and hungry.

(Photos from 1970-71.)

……. on the next page, the 23rd Hour continues into the British Sector..

Click to continue…

Or return to 1915-1945…