These vignettes were written in 1993 as part of a longer paper for the twentieth anniversary of the “Energy Crisis”. The paper appeared in the CompuServe Military Forum and the CompuServe Travel Forum. However, the stories may also shed light for younger readers who were fortunate enough to miss the Cold War. The threads of the Cold War tie into today’s issues. The people in these stories are composites of real people.

From THE TERROR TAX — by R. W. Rynerson

Most of the taxes that we face at the gas pump are really user fees, turned back toward expenditures that benefit some part of the highway user community. Not listed is another assessment, the cost of financing international terrorism and the rapidly expanding Middle East war machines in one column, and the cost of defending against those threats on our side of the ledger. A cynic might note that, in effect, we are financing our own replacement for the late Cold War.

A QUARTER-CENTURY AGO

In the dim lighting of Berlin’s pre-World War II-vintage Frederichstrasse U-Bahn station, a young Frenchman dressed in the casual clothes of 1968 student-radical-chic passes easily through the station’s border inspection point, leaving the capital of the German Democratic Republic, and yet, through the shadowy quirks of East-West legalities, remaining in East Berlin on the subway platform. He is unknown to the police in the West, but is a friend of left-wing terrorists known to newspaper readers at the lowest levels.

Michèle M., a kindergarten helper in a West Berlin daycare, living there ostensibly to perfect her German, and holding identification papers created by the French Army, is also on the platform. She has been looking at economically-priced East German books at the platform newsstand which is accessible to westerners on the U-Bahn without going through the border controls upstairs.

The young man moves quickly onto a U-6 train headed for the French sector of the divided city, and just as quickly, Michèle boards the Tegel-bound train. She notices the young man shift uneasily in his seat; he touches his pocket, in which an envelope of random bills makes a suddenly uncomfortable bulge, then looks up at her. She smiles quickly, and then begins to read from her new book, making him feel that HE is following HER.

Subsequently, a French intelligence agency files Michèle’s information that another envelope of Western currency is back in circulation – diverted from the struggling East German economy to finance terrorist bombings, assassinations, and sabotage in Western Europe.

This scene is familiar to anyone who reads spy novels, and as with many of them, is based partly on real events, which governments usually pretended not to see. Why did they play this game? Because it was seen to be in our national interest not to respond directly – the men who counted out the bills in the young man’s envelope were backed by chess players in the Kremlin who controlled nuclear weapons. Each side moved pieces obliquely on the board. EACH HAD SOMETHING THE OTHER SIDE WANTED AND/OR FEARED.

Decisions by Western leaders helped to create this situation. Similarly, our leaders’ decisions have helped to build the new threat of oil terrorism.

TEN YEARS AGO

Around the U.S. and Canada, cheap gasoline and massive highway projects smoothed the move of populations beyond “traditional” suburbs and pushed jobs into other suburbs. Older shopping centers of the long-ago 1960’s and 70’s were left rotted out. Within a decade, trends that had been gradually accommodated burst into rapid moves that shifted most of us into complete dependency on the auto – some of us not even realizing that we had moved our entire lives into zones where there is no practical way of providing alternative transportation without massive subsidies.

In many of the new suburbs, some temporary oil market shift like the 1973-74 crisis cannot be handled by a partial shift to public transport, walking and bicycling. In today’s low-price energy world, the service planning department of Denver’s Regional Transportation District receives a steady trickle of despairing phone calls from people who have lived in the auto-only suburbs and suddenly find themselves unable to drive, or who do not want their children driving to the mall.

A few new neighborhoods have been built so that the answer to the phone call may give the caller hope – they have sidewalks, they have a logical way for a bus to get into their neighborhood, the light rail line is inching toward them. Others are not so fortunate. Their lives are tied on the end of a string of oil pipelines and tankers that in turn depend on a U.S. fleet churning the waters of the Middle East and on recycled Cold War agents fighting a shadowy war with terrorists and their oil-financed sponsors.

In the 1950s, national defense was used as an argument for dispersing urban population. Today, that very dispersal threatens our national defense.

THE TORCH PASSED – Two decades ago, that was…

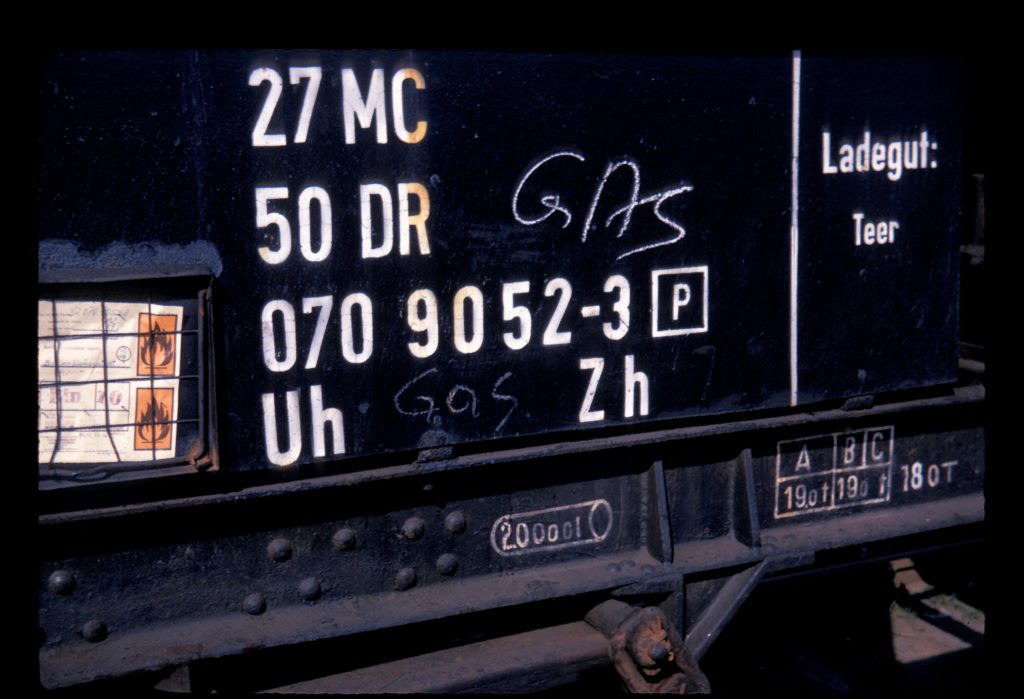

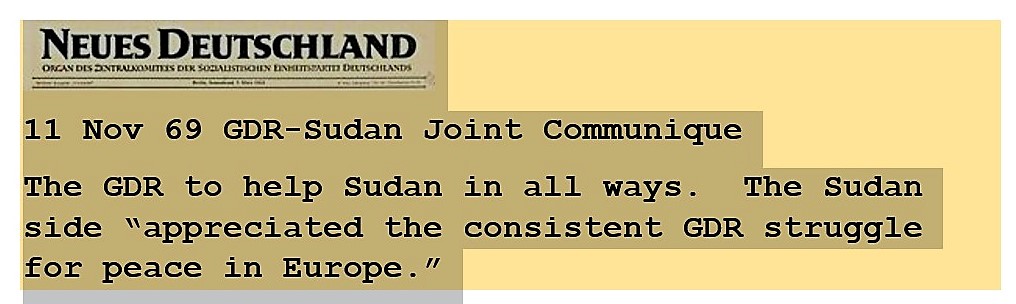

Khartoum’s airport at 02:20 on a Sunday morning was not the best place to be, but Werner Schmidt was there, just doing his duty. Ostensibly a driver for the German Democratic Republic’s recently-expanded embassy, he was there to meet a special passenger coming in on Interflug Flight 780 from Berlin. A British businessman also waited for an incoming passenger on the flight.

The Brit made Schmidt nervous by being too gregarious (“I’m Harry Axton! And what’s your name?”) and making provocative jokes – teasing him about the arriving airliner being Soviet (“Well, better a Russian plane maintained by German mechanics than a German plane maintained by Russian mechanics, eh?”). With relief, Schmidt picked out the sound of the Ilyushin 18’s turboprops. They whirled to a stop and bleary-eyed passengers stepped out into the lights.

Herr Schmidt spotted a short, professorial-looking man, carrying a leather case. This “agricultural chemicals” expert recognized Schmidt and was quickly whisked through the border formalities. The way was smoothed by a Sudanese official from the host government’s intelligence service.

“My chap never showed! Good show that yours made it,” the Brit exclaimed as they rushed past him into the GDR embassy car. Herr Schmidt forgot the boisterous businessman almost immediately, remembering him only in the category of general nuisances in airports. Harry Axton, in the meantime, forwarded his report on the arrival of the chemicals expert to the U.K., where people with a professional interest in tracking explosives experts filed the information.

“If the Sudanese would have had a bomb-sniffing dog on duty at the airport that night, it would have bit Jerry’s hand right off. I think that I could smell the ‘eau de nitrate’ off that man myself.” Harry said this later to a colleague and then raised another beer to his sweaty lips.

Herr Schmidt’s unnamed passenger avoided bomb-sniffing dogs and had a productive, if just-as-sweaty-as-Harry, stay in the friendly Sudan, teaching his bomb-making skills to people who his government saw as oppressed by Western colonialists, people who might be used to disrupt Western oil supplies or economic moves. Perhaps he came to realize that these people were using HIM, gaining weapons to use in punishing those whom they saw as enemies. As obnoxious Mr. Axton probably said, “…the torch had been passed.”

In the decade that followed the collapse of oil prices, a series of “small-scale” wars and terrorist actions have left uncounted people in the Middle East and elsewhere dead, maimed, or homeless. They have become pawns in a new type of international chess game developed to replace the crumbling Cold War.

This game is focused on our continuing need for imported petroleum, which has replaced our fear of massive nuclear destruction as a restraint on how far the United States can push its national will on others, and as a means for enemies of the West to make us uneasy domestically, at little risk to their own governments.

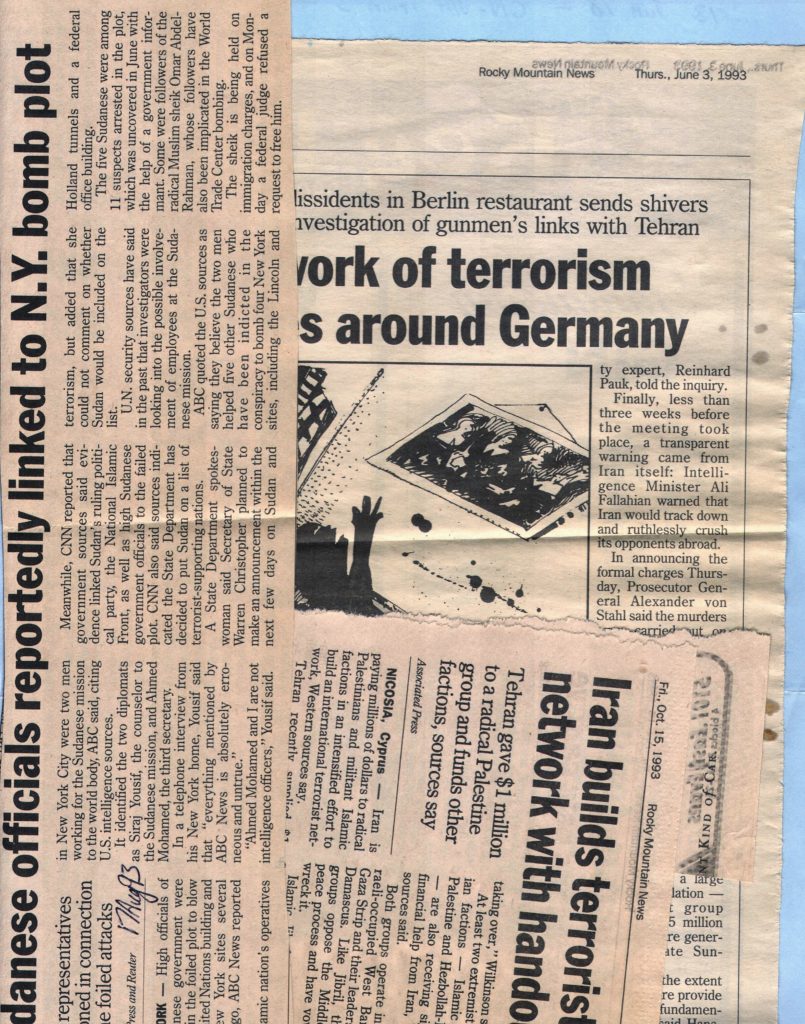

Instead, we are settling into the replacement for the Cold War chess game. Certain countries with dangerous governments need our billions of dollars worth of oil purchases. For example, Iranians need it for their domestic economy. They also need it for making the payments to the Russians on their new naval fleet. Therefore, they dare not confront us directly. In turn, as long as they do not do so, they are free to act out their hatred of the West through intermediaries. Our very dependency on them makes them contemptuous of us, much as a drug dealer might scorn his clients’ disgusting eagerness.

Thus, in 1992 Lebanese expatriates gunned down Kurdish nationalist leaders in a Greek restaurant in Berlin. Iran, which has a “Kurdish problem” inside its borders, had warned through Intelligence Minister Ali Fallahian that it would track down and destroy its opponents in foreign countries. [In March, 1996, German authorities issued an arrest warrant for Fallahian in the 1992 bombing. No arrest is expected soon.] Similarly, the World Trade Center bombing has been linked by authorities to people from weaker Islamic countries, not Iran.

In running through news computer files while writing this article, a pattern appeared: a dire semi-official warning from Iran, an assassination or a bombing, and then a denial from the handiest Iranian ambassador, emphasizing that the suspects were not from his country. The Iranians have learned to play the Cold War game of action through third parties. Whether they are more astute than the Libyans and Iraqis at taking the West’s money while attacking their customers remains to be seen.

TODAY

Oil money is flowing back to the Western world and the former Communist block in the form of weapons sales revenues. The Arms Control Association, according to the Associated Press, reported that since August 1990 U.S. military export agreements alone totaled $39 billion. The same AP story (11 Aug 93) quoted Kamel Abu Jaber, Jordan’s former foreign minister, as telling an interviewer that, “the Middle East is a powder keg, and to put more weapons into it will add to the horror.” Even lowered oil revenues can be used for weapons, especially when one has a civilian economy too small or too repressed to absorb the Western payments.

Two decades after the Energy Crisis began, Chevron Corporation Chairman and Chief Executive Kenneth Derr boasted that the world has enough oil to supply the next half century, according to a Reuters report on September 21, 1993.

“Moreover, if our reading of the market forces is correct, this era of stable and affordable energy should continue far into the future. Only external forces could change that picture,” he said.

In Kenneth Derr’s world, Iran will continue jockeying with Iraq and other oil states to be that external force capable of bending the Western nations to what it believes to be the will of Allah. At home, Americans, like those in Boulder County, Colorado today, will face the environmental ravages of oil exploration and recovery done “on the cheap” to compete with the vast black pools under the Middle East. Americans and Canadians and Europeans will from time to time be expected to die in terrorist attacks or small wars.

We have proved to be very courageous and ingenious people when confronted with an emergency. Whether we must wait fifty years, until we have almost completely disabled ourselves through suburban sprawl and auto dependence is the major question. Whether we must maintain a major military establishment and extreme security measures for another fifty years is another important question.

While you are reading this, in a dark corner of the Arab district of France’s St. Genis-Laval, an older man is handing an envelope to a student from Tunisia. The older man flashes back for a moment in his mind to his first meeting with the East German chemical expert, his teacher, in Khartoum in 1971. He was just as nervous then as this young man is now.

The envelope contains dollars – oil dollars from Iran, money extorted from wealthy overseas Arabs, and conscience money collected (on the Irish Republican Army model), through “charitable” front groups in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere [NOTE: the latter source is fading as oil prices drop and public awareness grows]. Each of these dollars is from the “Terror Tax” added to a tank of gas at your neighborhood filling station.

In another hour, the young man will be on a train, moving indirectly toward an Air France flight timed to hit Kennedy at the busiest hour for customs inspections. He will shift uneasily in his seat, the envelope seemingly too big for his pocket. From a nearby seat, a nicely-tailored, fortyish, Frenchwoman will glance across at him. Apparently she is a school teacher, from the papers and books the young man will note that she carries.

As the train begins to roll, Michèle M. will watch the lights of the station shed play across the young man’s face, and then she will write her notes in the pretend school papers. She feels a little tired, after a quarter century of this game. Her report will be placed in the proper file.

$ $ $ $ $

This paper is copyrighted in 1999 by the author, Robert W. Rynerson and may only be reproduced under the provisions stated on the Home Page of the Berlin 1969 web site. With typos corrected, it is copyrighted in 2008 and 2019. Although the material in it is now dated, the original analysis has been left as first released in order to reflect the point of view of the era when Western leaders averted their attention from long-range energy problems.

For permission for other uses, contact the copyright holder at rw.rynerson@att.net and provide information as to your planned use for the paper.