Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of my enemies…

— Psalm 23: 5, Revised Standard Version

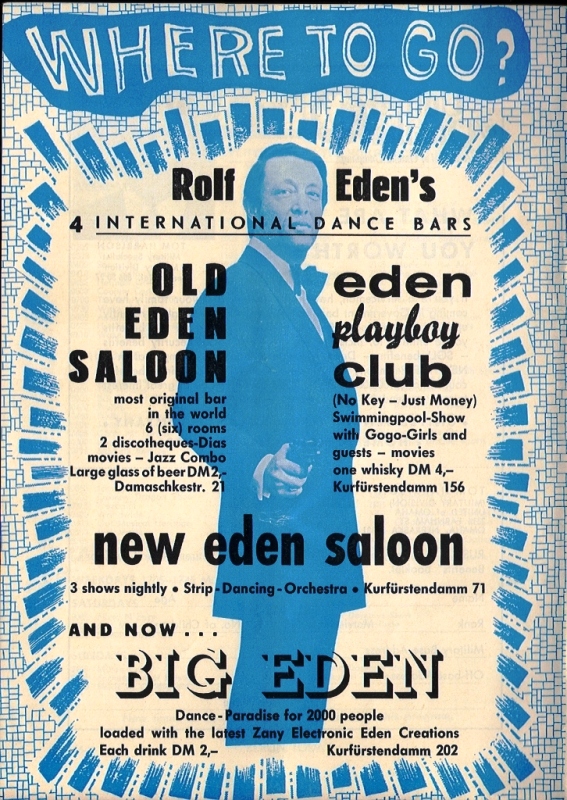

This section takes us into the British Sector and the Ku’damm. For English-speaking readers, ‘Ku’damm’ is Berliner slang for Kurfürstendamm. The Ku’damm had many identities, with upscale shopping and restaurants during the day, elegant dining and entertainment in the evening, and some other activities in its darker corners. For many GI’s, it was the ‘Q-Damn’ that they associated with “going Downtown” in Berlin.

— R. W. Rynerson

Every other corner along the way to the Ku’damm seems to have a neighborhood pub (‘kneipe’) marked with an illuminated sign sponsored by the brand of beer on tap, but otherwise lights are dim. Shadowy pedestrians can be seen in between tree trunks and the lines of parked cars, but the predominant feeling in these streets is that everyone with any sense is at home upstairs above the shuttered storefronts.

Our chauffeur claims that a team of British soldiers — taking advantage of their strategic location in the center of West Berlin — had set out to have a beer in every pub in Berlin, but gave up when they realized that new ones were replacing old ones faster than the Brits could get round to them.

He shifts down to slide his VW through the last of the peculiar Berlin traffic signals that tip motorists to the coming green by means of a flash of yellow below the red; unexpectedly the Ku’damm opens up before us. It is a wide canyon of light after traveling block after block of the five-story apartment buildings squeezed onto tired streets. In contrast to the sleepy side-street pubs, the restaurants and bars along this great way are either closing for the night or jumping with activity.

There is a “Hollywood parking place” open at the corner of a cross street that is otherwise still packed with cars. Americans like us would call it a “parking space” or a “place” to park. Berliners — having become used to overparked streets — call it an “opening” or a “gap” and that explains why our guide demonstrates how to turn sideways while getting out of the VW without banging the door on the street furniture next to us. The parking space required pulling up on the curb.

We thank our driver, who is headed to meet a friend at the pizza place a short distance away. Italian immigrants are now introducing pizza to Berlin and just in time, from our driver’s perspective, because it reminded him of home and a certain girl back in an Italian neighborhood. We — according to our guide — will be meeting a couple who are friends of his at the recently renamed Alt-Berliner Biersalon. It is at a convenient location and despite its renovation is descended from a genuine old-Berlin restaurant, which our guide defines as anything that opened for business before World War I. In this case, the establishment we will be visiting made it in under the wire: it started up in early 1914.

Thanks to the miracle parking space, it is only a short walk to our rendezvous, but our way is interrupted by a sleazy looking Berliner handing out cards promoting an off-Ku’damm strip club.

“Hey! American friends, how ’bout them Brooklyn Dodgers!” He speaks 1950’s GI English. “Hey, buddies, I can get you a deal for more action than you can handle.”

“Not tonight,” retorts our guide, causing us to wonder if he really means to come back some other night.

“See you later, alligator,” sing-songs the strip-club tout. He must be used to rejection, as his sales approach invited it.

Past him, a shopworn streetwalker half steps out of the doorway shadows, sees that we are walking with a purpose, and drifts off to share a smoke with a colleague.

Our guide signals a halt outside the Alt-Berliner, so we can take a look around at the intersection that has become the center of the spun-off city called West Berlin. The street around us is undergoing a change in character, like a dissolve in a movie. Beneath our feet, the last U-Bahn trains are rumbling out toward the outer boroughs. The last regular buses are leaving, and with them, the people who have a life in the daylight are leaving.

The first of the owl buses, known as the “Nachtwagen” appears on its mysterious way. The routes these buses follow do not all match the daytime lines, so customers must be clear-headed and reasonably awake to make use of them. One of our group remembers the drunk who was put off the U-Bahn at Krumme Lanke. Is he somewhere on a Nachtwagen headed down unfamiliar streets to an unexpected destination?

An elderly newspaper vendor appears with a few of tomorrow’s papers. Were the night people who are gathering along this street already here — lost in the reveling crowds along Berlin’s broad way — or did they only emerge at the 23rd hour? Our guide is not certain, though he does recall that his mother treated them in her city with Christian respect. She saw them as residents of a different culture that operates on its own social rules and logic, but with the same humanity as most of the rest of us. We see a police VW slowly cruise by and an officer nods his head at an old lady shuffling on some errand. She winks at him — twenty years old for a moment — and then hunches over to shuffle further down the side street.

The doors to the Alt-Berliner Biersalon swing wide as a bleary-eyed party exits. Their unfamilar dialect marks them as visitors from West Germany. We enter and walk to a table halfway back in the restaurant section. A young couple look up from their intense conversation. Our guide gives them a familiar wave as we approach to meet them.

“This is Bob, err… Robert,” he says, and the tweed-jacketed young man rises to shake hands, German-style, though he seems to be American or British.

“And this is Michèle.”

https://www.alt-berliner-biersalon.de/

“And this is Michèle,” our guide repeats himself. It’s the first time this evening that the glib young man has showed nervousness. Our eyes follow his to Robert’s companion, whose softly accented greeting and manner of dress establish — certainement — that she is French. This is a bit disorienting, as there is a well-established stereotype of the American with a German girlfriend in Berlin.

As our guide observes later, French women seem to be able to do a great deal in terms of style without wasting money. About 20% of German women appearing around us this evening seem to know how to do this, whereas — he claims without reference material — 80% of French women can add a scarf to a plain outfit and make it into a fashion statement.

Michèle’s style tonight is disrupting traffic in the restaurant because she is wearing a maroon jumpsuit. None of the German women are wearing maroon — perhaps Michèle chose it because it sets off her hair color, or perhaps she chose it because none of the German women would be wearing maroon.

The traffic disruption, however, is due to another feature. The well-fitted jumpsuit is held together by a torso-length zipper with a big, brass-colored pull ring. It is snug up to her throat. So… there are plus or minus twenty Berlinerinen still in the steadily emptying Alt Berliner Biersalon dressed for the night out that they are winding up — all showing various amounts of flesh — and their men keep sneaking looks across the room at modestly tailored Michèle and her brass ring.

In the nature of Berlin conversations, we notice that Robert, Michèle and our guide communicate in a mixture of English, French and German. It turns out that when one language doesn’t work, they rewind the discussion and start anew in another language, or they reframe their sentences. They appear to be completely unaware of this. It’s second nature, our guide tells us, for the international segment of Cold War backwater Berlin, because there are not enough foreigners of any particular nationality outside of the military and diplomatic housing areas and compounds to permit completely monolingual cliques to form.

The conversation revolves around what life in Berlin is like, or what if feels like to these bright, young pawns in the Cold War game of three-dimensional chess that they inhabit. Berliners, we conclude, have worked hard to make the place comfortable. But just when one starts to relax, someone with an issue comes along to demand attention. Some of those who demand attention are willing to pull a trigger, such as the neo-Nazi who shot a Soviet guard in the British Sector a year-and-a-half ago. Some of those who demand attention are not even clear as to what they demand, such as those behind the torching of luxury cars that recently has become a common occurrence.

Others — such as the ruling circles in East Berlin — could go on at great length and send foreigners digging for their dictionaries with what our guide calls “20-Mark words”. All those words, of course, being lost on West Berliners when traffic signals at the Autobahn checkpoints suddenly turned red for the already jammed traffic at Eastertide. Communist rhetoric spun aimlessly when smirking guards smoked and chatted under the frozen stop signal.

We are just trying to learn a bit more about the couple who are going to guide us on the last leg of our nighttime traverse of West Berlin when a wave of customers of a different type flows into the restaurant. The new group draws the attention of the few customers who remain: the newcomers are painted ladies and their shifty-eyed pimps.

Robert, Michèle and our guide are all surprised by this. Not surprised that there is prostitution in West Berlin, but that this well-run restaurant turns out to be a spot favored by this branch of the demi-monde for a rendezvous. And it’s a rendezvous in the same sense as the fur traders of the Old West understood the word. This is a business meeting, a social event, and a way of checking in and cashing out.

Robert, it seems, can explain what Germans call die Lage, the situation. We learn that he works for one of the many ad hoc and/or cut-rate intelligence operations spawned by Berlin’s pivotal role in the Cold War. Because of the politics here, he explains, the Western Allies will not permit the West German style of organized, public-utility sex. Instead, in West Berlin this service is provided by unregulated entrepreneurs as in the United States, though more openly. When someone mentions that this tolerance policy is hypocritical, Robert points out that in East Germany the system goes beyond hypocritical by arguing that the problem cannot exist in a Socialist state. This does not account, he dryly notes, for the Berlin Brigade G-2 Patrols’ reporting that clusters of tarted-up women could be seen loitering around the Ostbahnhof, perhaps waiting for their country cousins to arrive. Our table conversation turns to how social issues are dealt with in our different cultures.

Berlin, our guide quotes someone whose name we forget, is a city where restaurants, rather than coffee houses, are the home ports for many. Here on the Ku’damm we can sit for hours, analyzing the situation, gnashing our teeth at the weather, talking about friends or colleagues, and so forth.

Outside — though it is still warm — there are fewer pedestrians. Doubledecker buses that flowed in a yellow river past the windows of the Alt-Berliner now pass only sporadically. Inside, we’re high on conversation, helped along by another dessert or another beer or another coffee or another.. Do the people around our table need to go to work tomorrow? (Well, not including the streetwalkers.) If they do, their heads will be somewhere else, perhaps still swirling through these conversations.

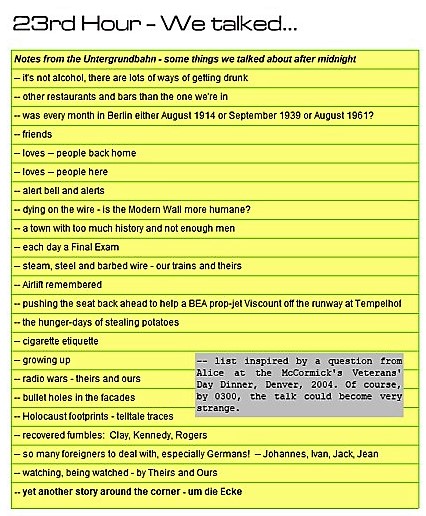

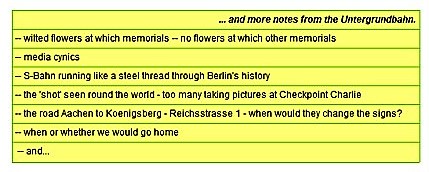

Our own table has covered so many things– or perhaps uncovered them. With no agenda to follow, you may later realize, there is no responsibility to resolve issues or come to conclusions. This is at once charming to North Americans [and frustrating before the invention of Starbucks]. The idea that issues flow like that endless river of yellow buses is novel– but alien — to people who want to turn dinner conversations into a business meeting. If you had tried to take notes, more topics that we may have covered are inked below.

And, we talk about the Berliners. That is not surprising, because there are so many of them. Or perhaps it is because Elisabeth came over to our table to say hello.

Elisabeth is a Canadian expatriate working for an American company in Berlin. She has a couple of academic degrees, but that has not dulled her common sense, our guide comments after noticing her. Somehow, he knows her, perhaps from standing in line with her at the Pan American Airlines city ticket office. That was one of the places where military personnel crossed paths with civilians. Our guide invited her to pull up a chair for a moment.

“These people,” he points to us, “are visiting Berlin and trying to learn what the nights are like here. I’ve been taking them around to see what we military people are doing, but what are “normal” people talking about tonight?”

Elisabeth laughed and tossed back her head back in a way that showed off her dark hair. For a moment, Michèle was not the center of attention. A couple at a nearby table noticed us and began to furtively glance our way as Elisabeth proceeded to talk about “normal.”

Among the candid conversations in Berlin nights were the discussions by Allied personnel, military and civilian, of the joys and frustrations of working with their German colleagues. The following is the actual text of a Canadian’s description of her work situation in a German-filled office. Some details have been changed to protect the guilty or innocent. This might well have been the topic of the over-the-table discussions in the Alt-Berliner Biersalon linked with this page. And, “natuerlich” at another table we may surmise that Berliners were talking about the joys and frustrations of working with their Allied colleagues.

Somewhere in another corner, there was an IM (inoffizielle mitarbeiter) making notes to report to the Ministry for State Security (MfS) over on the other side of the Berlin Wall. We know today that this sort of report was over-valued in the confidential summaries circulated to Communist leaders, who over and over heard that the Allies and the West Berliners or the West Germans were on the verge of a divorce, rather than a lover’s quarrel.

“You do lead a ‘normal’ life, don’t you?” Robert grinned as he asked the Canadian to tell her story.

Life of an Expatriate

“Well,” Elisabeth began, “that all depends on your definition of ‘normal’.” She returned the grin to smiles around the table.

“I think I live a fairly normal life, though I have moved around quite a bit. I spent some time traveling around Europe before I moved here, but I guess one is never fully prepared for this place.” There were nods of agreement around the table.

“Take the subtleties of language, for example. I don’t think I’ll ever get them all in German! Even the differences between Northern and Southern German are hard to get hold of. I’ve found that in Berlin, the accent and the slang make it seem almost like a different language than that spoken in Munich. Perhaps the biggest problem is that most of my German friends want to improve their English, so… you know how it goes!” Even Michèle nodded at that.

“I don’t know if it’s the same in Munich, but I do find Germans a bit difficult to know… you have to be around for a while before they really open up.”

She continued.

“Life as an expat is probably easier than if I’d just come over on my own.. we do get ‘perks’ such as company cars, tax breaks and help with the whole immigration thing. Still, one has to do the mundane things like getting the phone in, shopping, dealing with the hausmeister… it’s really no different than at home except that there is the language thing to deal with. Oh, and did you know that when you rent a flat you don’t get any closets or a kitchen? … Furniture stores do a booming business!” She paused for a moment and as we reflected on what she had said, there was unusual silence around our table. We could see that the Canadian was thinking about something deeper than closets.

“Cassette tapes have helped, they’re a good way to stay in touch with family and friends at home, and I’ve met a few new ones as well!” Elisabeth brightened as she nodded toward the companions over at her table.

“The biggest frustration I find is “the rules” … if it ain’t in the rules it can’t be done and I see that stifling some creativity in our office. Marketing has to be a creative thing (“…sometimes *too* creative” she interjected into her own comments) and in our business, you have to find a way to get it done even when it looks like there isn’t a way. The Germans will tell me it can’t be done and they get quite annoyed when I tell them it *can* and they have to find a way. It is definitely a cultural thing and probably the cause of most of the problems in the office.” She looked across at her German tablemates, who looked curiously back.

“Hmmm… I seem to have run on a bit, sorry.” We murmured that, to the contrary, her comments had hit a lot of nails on the head. “As for ‘normal’ lives….. I’d be interested in hearing about your cloak and dagger escapades someday.” Our guide and Robert rolled their eyes. “I’ve spent quite a bit of time in the Soviet Union,” she continued, “and had a chance to experience some of what happens to people in their personal lives when big brother is always watching.”

And, knowing that she would not hear any cloak and dagger stories this night, she excused herself and returned to her table. The older couple at an adjacent table — who may have been eavesdropping — looked hastily down at their unfinished beers as Elisabeth spotted them in passing.

Time to Go

However, even the most determined conversationalists become tired. Or perhaps the cumulative effects of beer, pastries, coffee and tobacco smoke and the late hour is taking a toll. The streetwalkers and pimps have settled their accounts. Now, only the debris of diners past marks the tables where world affairs and community issues were being settled. As if on an alert bell of their own, the waiters are caught up in a frenzy of table clearing. It is time for us to go.

Bibliography:

Craig, Gordon A.; The Germans; Penguin Books; New York; 1982; 350 pages paperback.

Knabe, Hubertus; West-Arbeit des MfS: das Zusammenspiel von “Aufklaerung” und “Abwehr”; Christoph Links Verlag; Berlin; 1999; 598 pages.

Mueller-Enbergs, Helmut; “The Place of Unofficial Employees (IMs) in the GDR’s System of Governance” published in The Journal of Intelligence History; Lit Verlag: Dr. W. Hopf; Berlin; Vol. 8 No. 1; Summer 2008; page 67.

Murphy, David E., Kondrashev, Sergei A., Bailey, George; Battleground Berlin: CIA vs. KGB in the Cold War; Yale University Press; New Haven & London; 1997; 530 pages.